I Heard Her Call My Name: An interview with Lucy Sante

interview by Vicky Oliver and Charlotte Slivka

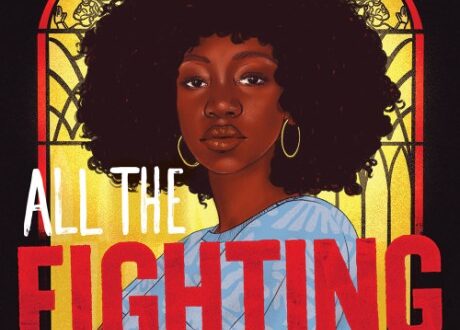

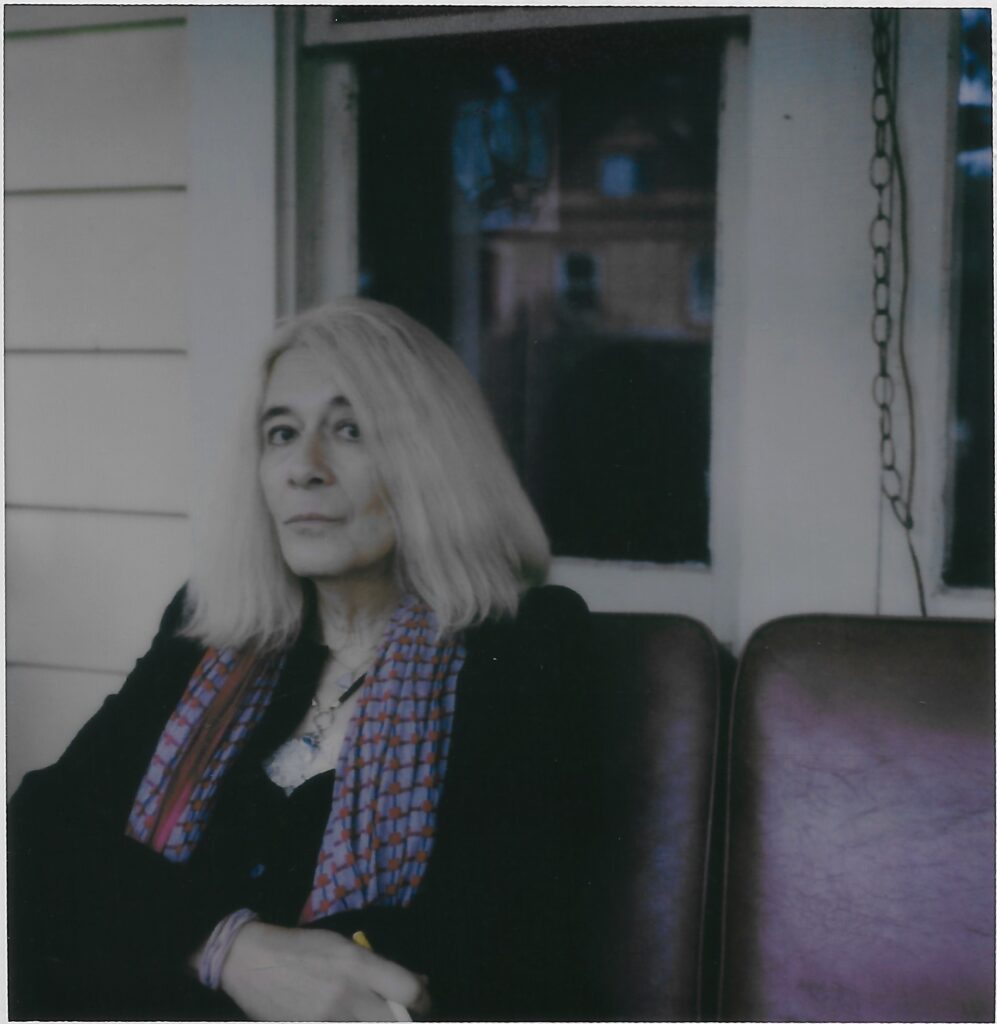

Lucy Sante has had a long and decorated career as a chronicler of the arts and their environments. From her books including Low Life, Evidence, and Kill All Your Darlings and the pages of the New York Review of Books, she has amassed a devoted readership of her criticism and cultural commentary, assiduously sharp and brimming with curiosity. But for a long time, while in pursuit of artistic truth, she felt unsure of her place, eventually coming to understand that she was evading the truth of her own gender identity. In her remarkable new memoir, I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition (Penguin Press: February 13, 2024), Lucy Sante writes about finally turning to face who she really is.

Editor-in-Chief Charlotte Slivka, and nonfiction editor Vicky Oliver sat down with Lucy to chat about her new book, her transition and writing, and techniques for tapping into the unconscious.

LIT: Was I Heard Her Call My Name harder to write than your other books because it was so personal?

Lucy Sante [LS]: No. Exactly the opposite. It was way, way, way easier to write. I’ve never written anything as fast in my whole life. It just came out fully formed. It took me—I think it was less than two months. It came out all at once. I was writing—which I never do—morning, noon and night, literally.

LIT: Now that you have changed your name how has your public identity been impacted by the name change? Have there been any surprises?

LS: Absolutely not. I think, in part because of coming out on Instagram, followed by my piece in Vanity Fair, which everybody and their cousin in America seems to have read, so everybody in my life, however remote, knew about it. It’s been at least two years since anybody expressed surprise. So no, it never affected my nom de plume. I never heard of people not being sure of Nineteen Reservoirs because it was written by someone close to my name. So it hasn’t been a problem in the world. It was a problem I was having with myself, which I go on to describe in a chapter in the book.

LIT: Your writing life is a journey and your transition is a journey. Where do those journeys intersect, if at all, and where do they diverge?

LS: Well, they’re two different, if both essential, parts of my being. They’re going to co-exist. About like ten milliseconds after my dam burst, I started thinking about writing about it. That’s just the way I’m built. It’s who I am. I’m a writer. Let’s see, my egg cracked in February ’21, and I finished the book in December ’22, so that was the gestation.

I wanted to keep my account concise. I wanted it to be a quick read, but it contains the essentials. There isn’t anything hidden. I don’t have anything left to hide. Will I ever write about being transgender again? I know what my next three books will be, and none of them is about being transgender. It’s a fundamental part of my being, but so is my being a Walloon, and that has only shown up in one book.

As I say in the book, my friend Darryl Pinckney declared twenty-five or thirty years ago that he was not a gay writer, he was a writer who was gay. And in the same way, I am a writer who is trans. There are trans writers who are writing for a trans community, but I’m not doing that. I’m forty years older than that community.

LIT: You wrote in the book: “I was still very much aware of the presence of Luc, whom I sometimes like to think of as my sad-sack ex-husband. It would happen to me that if I had been writing or had gotten into a conversation about books, say, I would suddenly look up and realize that I felt genderless.” We were hoping you could elaborate. What does it mean to feel genderless?

LS: Well, it’s impossible for me to spend very long without thinking about gender nowadays. Previously, when I was trying to be a male, I would shrink from thinking about gender. This involved a strategic retreat into an invisible third-person narrator mode, in which I had the gender of the angels. Sometimes I’ve been working away on something, and it occurs to me that I haven’t thought about gender in the last two hours. Holy cow.

LIT: I love that, “the gender of the angels.” That’s so interesting, so you’re sort of saying that it’s freeing you to not think of gender at all.

LS: Yeah, kind of. Although these days I really enjoy it. That’s the difference. Back when I was trying to be a guy, it was painful. Now it’s a pleasure.

LIT: It seems like when you came out to yourself it was akin to lifting the lid on the self as a contained being. Was the cracking of the egg also a cracking open of the self? And if so, can you say more? Do the illuminations keep coming?

LS: Yeah, of course it was. I mean, it couldn’t be one without the other. It’s not possible. You know, it was the total package. And of course the big, huge realization was how much my entire life had been determined—my whole inner life had been determined—by trying to keep the lid on this thing I’d known about myself since I was like nine.

By the middle of my life it was all about counter-espionage, it was like a Le Carre novel—layers of the onion—I was protecting the protection. The effort of suppression just came to determine everything about my personality.

There is still an inner core which is still the same person. But the fact is that I’m on the outside now what I always was on the inside. What I wore on the outside was this cloak of invisibility, which was kind of a boon in some ways but definitely a deficit in others, and I’ve realized that holy shit, I do have an integrated personality after all, and I kind of like it.

I just wish it had happened earlier, but what can you do? One thing I’ve got to say about the book: it’s been over a year since I turned in the manuscript. I’m constantly aware—did I make false claims? Did I, like, bank too much on something that was not going to happen? The one thing I keep coming back to is my assertion that I got rid of my neuroses and replaced them with “ordinary human unhappiness.” The fact is that while I did get rid of a lot of neuroses, there are also neuroses that have nothing to do with gender, and they’re still sticking around, believe me.

LIT: In your book, The Other Paris, you wrote: “the past is hardly a single era, after all, but combined, composted layers of a thousand eras.” Would you say the present “Lucy the writer” is a conglomeration of eras, or something altogether new?

LS: Sure. I’ve certainly been through a lot of eras in my time, as well as a number of places. Place is very important to me. And people I’ve hung out with. All these things cut roads through me. They’re all still there, of course. This new me, well, this new me is still very new. It hasn’t quite been three years since my egg cracked, after all. I have a long way to go. I haven’t lived that long as this person. There’s a lot of experiences I haven’t had yet as this person.

LIT: When you say, there’s a lot of experiences you’ve haven’t had as this person, I’m just curious as to what that means.

LS: Intimacy. I haven’t really had intimacy in this form. To cut right to the heart of the matter. That’s a big one. I’m sure there are others, but that’s the one that’s in the forefront of my mind.

LIT: You wrote, “Who am I? is a question I’ve been trying to resolve for the better part of my life, even without reference to matters of gender. I’m a writer before I’m anything else.” As a writer, how often do you write? Do you wait for the muse, or do you sit down every day and write? Has your writing process changed since transitioning, or is it pretty much the same as it ever was?

LS: I have no set schedule: I never have. As someone who began subscribing to Writer’s Digest at the age of twelve, imagine how long I’ve been hearing or reading people say “you must write every day.” And I’ve never done that. Not for a minute. Unless I was writing something like this book, which, you know, I was writing for ten hours a day. It was incredible. Because I don’t do that.

I recently not only retired from teaching in 2023, I also retired from freelancing, which is not an absolute ban, but mostly, and that I did for over forty years. It conditioned me. I write for the deadline. And usually that means that I’m writing it as the deadline falls. I’m always late. Unless occasionally I get an assignment where I just sit down and write the whole thing at once. This happens sometimes. But I don’t write every day. I don’t even write every week. Sometimes I go long enough that I feel like I have to relearn to write when I’m facing the absolute deadline. But I do write things on my own initiative. But those, well, I have to play games with myself to do that really. And, like I mentioned earlier, I have three books to write now. I like the idea of writing books now. I was afraid of it for a long time. The only way Low Life got finished was because the wolf was at the door.

LIT: That’s an amazing book. You structured it really well, and there was just a propulsive quality to it that I really loved.

LS: Thank you. Anyway, I was trying to get it done very quickly so I could get back to my first novel, which was going to be the really important book.

LIT: I noticed in a few of your works, such as The Other Paris and I Heard Her Call My Name, you use a term, “negative capability.” I was very curious if you could say more. How does that work?

LS: Well, that’s from Shelley, Percy Bysse Shelley. Let me see. I feel like I should be able to give you the dictionary…the conventional definition.

LIT: I thought it was an original term.

LS: No, no, no. It means a certain permeability. A certain approach that opens you up. “The ability, which Shakespeare possessed so enormously, to accept uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

LIT: Thank you for that. I had this idea that in writing it meant reaching for one idea to end up with its shadow, like in a photographic negative. On page 18 of I Heard Her Call My Name, when you were talking about the lines of a poem you wrote that the band the Del-Byzanteens used for a song, Girls Imagination, you describe your subconscious as a “higher power.” You wrote: “here it had smuggled in a whole scenario I had rarely managed to explore even in the privacy of my own imagination, as terrified as I was of the implications. I shivered at the words: “so strange to be someone so life-like too early which perfectly described the state I found myself in then, and sometimes still do. It was nothing less than a founding myth, a sort of robing of the bride, an alchemical transition from male to female…” I was really caught by that word, “alchemical.” Could you speak more on your relationship with your higher power and how it works in your writing? Are you more aware of how to work with it now, or do you continue to be surprised by it?

LS: It continues to surprise me. But I am more able to steer it nowadays. It took me a long time. It was the longest learning process in my overall education as a writer—learning how to fruitfully use that unconscious. How to go for simple organization that will put up walls such that the imagination will have something to bash against. And generally, trusting my unconscious, that’s the key part. It was always there, always buzzing around, but I didn’t always want to pay attention to it because I was being too cautious. That’s the thing I think a lot of people do. They don’t want to trust it.

I’m reminded of one of my favorite pieces of writing, an essay I think I assigned to every writing class I ever taught, called Comedy’s Greatest Era by James Agee, which describes, for people who had never seen silent comedy—before TV, but in the 40s—he’s describing silent comedy, making it visible to the reader. It’s a tour de force. There’s this bit where he talks about how crazy the early film studios were, when they were making these two-reelers, and they were completely collaborative enterprises.

Legendarily, there was on set someone known as “the wild man.” And the wild man was someone barely articulate. He practically had to be caged. And you’d finally get him to sit down and he’d say “You take…” And suddenly everybody knew what he was talking about. This is the kind of mythological personification of the unconscious here. The unconscious is that wild man sitting up in your head—or wild woman, but I see him as a “he” because I think of R. Crumb’s Mr. Natural with his long beard and robe.

Anyway, it’s just amazing to me how I’ll write something that later turns out to be better than when I wrote it. And it also applies to making collages. Suddenly I’ll think, wait, why did I put all this—oh, I see, because they’re the same color, duh. You know, the unconscious really is the greatest tool if you allow it to be. Probably I shouldn’t be talking ahead of myself here, but I’m wondering if the unconscious isn’t maybe a bit more fully stocked when you’re older in years. That may be another reason why I’m relying on it more than ever.

LIT: How do you access it? I mean, do you dream? You know, the dream state, when you’re waking up?

LS: Yeah, I keep hearing that you should start writing in the morning when you’re not fully out of that dream state. I’ve never succeeded in doing that. No. It’s just letting your mind wander, really. And also, when you’re actually in the task of writing, it’s like being super alert to all the random signals that come through your head. You hear a snatch of a song, you see images in your mind from movies or from three weeks ago or whatever, and if you’re concentrating, you’re tempted to bat those things away, but actually, they could be a clue.

LIT: I find that to be really useful in life, as well as writing. Paying attention to random things, they sometimes turn out to the most important. I wonder if transitioning has made your use of the subconscious more acute?

LS: Feels that way. It truly does. No question about it. Now, whether this is coming from the Estrogen side of things or coming from the I-have-liberated-myself side of things, it’s almost impossible to know where the energy comes from exactly. Because these things are linked.

LIT: You mentioned in I Heard Her Call My Name and elsewhere that you transitioned but you did not change your speaking voice. To what extent, if any, has transitioning changed your writerly “voice.” Has your writing style changed in the transition?

LS: I don’t think it has; it has just become freer. And, as for my speaking voice, by the way, I was actually on the list to have the procedure done at Mt. Sinai. It’s a glottal thing they do…proprietary, done only one other place. I thought it was going to happen sooner because I signed myself up last spring. I’d hoped to have this voice procedure done before my book came out. But then I had to record the audio book. And, having recorded the audio book, I thought what the fuck, you know, the cows were definitely out of the barn now. So, why bother? So, I will manage not to have had any surgeries at all.

LIT: Yeah, you mentioned that you’ve done other voice work, too, right?

LS: I narrated a feature-length documentary. Yeah. I did plenty of stuff. I really really wanted to make that my career at one point, but it was way too difficult to break into a very closed world.

LIT: You wrote: “Another reason for my repression was my sense that if I changed my gender it would obliterate every other thing I wanted to do in my life. I wanted to be a significant writer, and I did not want to be stuffed into a category, any category.” To what extent are writers pigeon-holed today—put in categories such as “female writer, trans writer” etcetera? Is there a “male writing style” versus a “female writing style?”

LS: To answer the last question first, no. There are different kinds of consciousnesses. But, let me see…that was a whole lot of questions. Let me see if I can retrieve. What was the first question?

LIT: I’m sorry about that! My questions are like snails: they circle and circle and circle. To what extent are writers pigeon-holed today—put in categories?

LS: No, it was before that.

LIT: Oh, yes. It was what you wrote. You wrote, “another reason for my repression was my sense that if I changed…”

LS: Oh, that. That is absolutely true. It would have been impossible for me to transition in the twentieth century because I like women, and even Harry Benjamin’s protocols for gender change stipulated that candidates had to be attracted to the “opposite sex”—gender change would make them heterosexual.

But if I had transitioned, I already had enough of a reputation as a writer. However, I would have been forever lodged over in the transgender corner. That would have been my beat, and it would have been weird to be writing books about other subjects. And I just wanted to be a writer, whatever gender. By that, I mean that I had things I wanted to say. I enjoyed playing with language, and also I wanted to enter the field of contest of my predecessors. That was very, very important to me. And I do come from a particular, or actually a few intersecting corners of the literary globe.

The things that interested me when I was seventeen are still the things that interest me now. I’ve expanded a bit, but I haven’t taken anything back. Anyway, no, I don’t think there’s a difference between male and female styles.

As far as this book goes, I see a direct continuity in its music, in its phrasing, in its forms of address. I’m still the same person in many ways. I’m also a completely different person. But as far as writing goes, time will tell. It’s interesting that when I came out to my ex, Mimi, one of the first things she said to me was, “So, are you going to start writing fiction now?”

LIT: You mention that in your book. It sounds like you are going to write fiction, right?

LS: Well, I already have, you know. Of my next three books, at least two of them are nonfiction: the first two. I don’t want to write a novel qua novel. That doesn’t interest me. There are some people practicing the novel form today who I love and think are first-rate. But for myself, I’m not interested in writing a regular novel. But I am interested in exploring the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction, as I have been for quite a long time really.

LIT: Would you call that autofiction? Or creative nonfiction?

LS: No, I would not. It’s not autofiction at all. That’s really not what I have in mind.

LIT: Would you call it hybrid?

LS: No. I would call it formalism. I’m a formalist. I’m old school. And yes, as far as all the categories that people put themselves into now, I guess it has to do with the difference between my youth, the world I came up in as a writer, and the way it is today. Back then, it was culturally central but economically fringe, a very small world when it came down to it.

There were only so many publishers, who published a limited number of writers. There were small presses, mostly in poetry. But in the late 60s, the major houses were publishing avant-garde fiction. They were not thinking of a mass market, although the avant-garde publications were underwritten by the success of, say, James Michener. And now, there are so many people that there’s been a major dispersal of energies. There are genres that I have never heard of that have zillions of adherents on Facebook or whatever. The day I walked into my local Barnes and Noble and saw an aisle marked, Teen Supernatural Romance…I had no idea what the hell they were talking about.

I come from that place called literary writing: literary fiction and nonfiction, and a certain strain of poetry.

LIT: You mentioned you have three books that you’re going to write. I’m hoping you can tell us about them if you can.

LS: I’ll tell you about two of them. The next one is actually the second book in my contract. The back story is that I got a contract not long after the death of Lou Reed to write his biography. And I knew right away that I didn’t want to do it, but couldn’t afford to give back what I had received of the advance. Anyway, I managed to swap it for two books, one of them this memoir, and the other one, since there has to be a Lou connection, is about the Velvet Underground in their time. That is the book I wanted to write in the first place. There are already twenty jillion books about the Velvet Underground, but the difference is that this will be a book about New York City in the 60s, which is something I’ve always wanted to write.

LIT: That sounds fascinating. Will you be writing about people like Angus MacLise?

LS: Of course. Totally.

LIT: I’m so looking forward to this book! When do you think it will be coming out?

LS: Well, my usual line is always, “oh, about a year after I finish it.” And then the book after that will be… a book about writing. I have a lot to say. I have many, many things to say. And I want to hit it before memory of actual teaching is gone from my mind. And, the book after that I can’t tell you about. That’s Project X.

LIT: Here’s one more question about writing after transitioning. I notice that books like Low Life and The Other Paris are very heavy with research and facts. These are amazing, compelling, page turner-reads but are also very, very dense with information. I couldn’t help but wonder, with the freeing of the self and the freeing of writing through transition how will that affect your relaying of research style.

LS: You know, 20-25 years ago, I had to stop people from calling me a historian. On the basis of Low Life, they thought I was a historian, which I’m not at all. I’m a writer. What I’m doing is evoking times and places. Very central to my vocation is a kind of time travel. The research I do: I don’t think of as research. Research is an academic enterprise, and it follows in an orderly fashion. You begin with a real question and follow an accepted procedure. I just don’t do that.

My books, Low Life and The Other Paris in particular, are books built on other books. They’re records of reading and absorption of nonliterary materials. I’m trying to conjure up atmospheres, and atmospheres have been a fascination to me since my early experience of bouncing back and forth between Europe and the US, a matter of both place and time. How is this year different from last year in terms of vibe? To do that, because I wasn’t there, I have to call in witnesses, meaning, usually, writers of those times, also, photographers and graphic artists.

I leave the meaning of it all to my unconscious. I do the research in absolutely no order. Writing about the events of my own life and calling strictly on my memory is a weirdly similar enterprise. I’ve never kept a diary, and I sold all my papers to the New York Public Library some years ago, so I don’t have letters from my friends to use for research, I just have to do it completely out of my head.

LIT: I’m interested in nonfiction and memory and how memory works. How memory can sometimes be a shadow of fiction or fiction a shadow of memory. Is memory curated? Remembrances…I mean, we can’t possibly remember everything.

LS: To my eternal frustration. I’m always trying to remember. Okay, I remember everything about that day except what shoes I was wearing. What shoes was I wearing? And it will drive me crazy. And at length I’ll come up with oh yeah, I was still in my Frye boots phase. I really try to remember everything. Do you know this amazing book, real cult book among my friends when we were young, The Mind of a Mnemonist by A.R. Luria? It’s a nonfiction account of a Russian peasant, who lived his whole life in a one-street village, and couldn’t forget anything. It made him miserable. If he needed to forget something he would have to dig a hole in his mind and bury it. One time he actually forgot something—it was because they were eggs, and they had just blended into the wall behind him. He had independently discovered the ancient art of memory. The Art of Memory by Frances Yates, that’s a key book. Beginning with the Romans—Cicero was the first to write about it—there was the science of building memory palaces. You established constructions in your mind, with all sorts of architectural details—colonnades, crenellations, staircases—and positioned the memories along those intervals, so that remembering was a matter of walking along these structures in your mind, picking them up as you went. That is a subject that has enthralled me all my life.

LIT: Fascinating. Topics for a whole other interview. I was curious how you came up with the structure for Low Life.

LS: It seemed just very simple. If I were designing an encyclopedia, like Diderot, say, I would start with the landscape, then go to the houses, then go inside those houses, then study the people… You’ll notice that the organization of The Other Paris is almost identical, although I was much more clear in my thinking when I wrote The Other Paris than when I wrote Low Life.

LIT: I want to throw it back to structure. I was thinking about something you said earlier, when you’re doing the research, you don’t follow any order. I guess you’re just following your curiosity. When you’re shaping your book, how do you find cohesion in what sounds like a kind of random process?

LS: When it’s a research heavy book, such as the Paris book or Nineteen Reservoirs, I keep physical notes on index cards. And then I go through them all and assemble them into possible categories. Then I shuffle the cards into those categories, and then shuffle them into an order within those categories. And that magically creates my structure.

Invariably, there are big holes I have to fill in because I didn’t think of this or that aspect, but really, it’s a matter of what I paid the most attention to. This is another thing that will go into my writing book, a thing I learned when I was reviewing movies, which I did for two or three years in the late 80s. I found it really hard to take notes in the dark; it would be this illegible scrawl. But then I realized that actually I was taking notes on all kinds of useless trash that would never make it into my review because everything that interested me I could remember. I could just rely on my memory. I never took a note after that. My memory was the filter that I needed.

LIT: Thank you for being so generous in sharing your time with LIT, I Heard Her Call My Name is an amazing book.

Pages 51-52 from I Heard Her Call My Name: A Memoir of Transition by Lucy Sante. Used with the permission of the publisher, Penguin Press. Copyright © 2024 by Lucy Sante

I did not have a strong gender identity when I was small. I drew pictures and played with my large family of stuffed animals, to whom I assigned family roles. I read the adventures of the boy reporter Tintin, but I also read the purely quotidian adventures of Martine, a sort of Everygirl, which must have been sent by a relative. I have a distinct but vague memory (I couldn’t tell you the year or even the country) of being somewhere with my parents and picking something up—a magazine? a record? —with a girl’s face on it, and them laughing at me. I certainly took it as a warning to avoid displaying pictures of girls—to not, say, tack up pictures of Françoise Hardy all over my room, after my paternal aunt and uncle, small-town newsagents, began sending me the French teen magazine Salut les copains. But I didn’t really know what the laughter meant. Were they laughing because it seemed suspiciously feminine that I would be interested in a girl on a magazine? Or was it because it seemed precociously heterosexual? That second one did not occur to me at the time.

But I was never pushed in any conspicuously masculine direction, either. Despite his interest in sports (he was an avid basketball player in his youth, although 5’2”), my father didn’t seem to care that I felt no pull in that direction, and we never engaged in the traditional male bonding experiences, not even tossing a ball back and forth. He also never taught me any of his skills: carpentry, plumbing, painting, paperhanging, even shoe repair (he had at one point apprenticed with a cobbler), although that had more to do with class than with gender. The way he saw it, I would grow up to be an important person who would have laborers to do those things for him. He was eager that I extricate myself from the working class and earn my pay from the comfort of a desk chair. He had no objections to my being a writer—he was a frustrated writer himself, who in 1948 had published an O. Henry-like sketch in a newspaper under the byline “Luc Sante.”

My mother never taught me her skills, either, not even allowing anyone into the kitchen when she was cooking. But then her mother and her aunt had been legendary cooks and she was forever made to feel like the graceless idiot daughter; her repertoire of dishes was limited to recipes written down by her mother. Naturally she would not have wanted to be observed in her daily race against failure. I’m certain my mother wanted me to be a girl.

Lucy Sante is the author of Low Life, Evidence, The Factory of Facts, Kill All Your Darlings, Folk Photography, The Other Paris, Maybe the People Would Be the Times, and Nineteen Reservoirs. Her awards include a Whiting Writers Award, an Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Grammy Award (for album notes), an Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography, and Guggenheim and Cullman Center fellowships. She recently retired after twenty-four years teaching at Bard College.