"All About Youth" by Fumiki Takahashi (translated from the Japanese by Toshiya Kamei)

All About Youth

Takehiko Nomi was behind the wheel of the Audi iX, and we drove up a lush green mountain road. The sunbeams shimmered through the trees and poured over the shiny red hood.

Letting the autopilot feature take over, Takehiko closed his eyes and sipped the hot cup of semi-strong coffee he’d purchased despite the warm weather. He eased his curly-haired head back onto the soft headrest. He seemed to contemplate the upcoming reunion, and I wondered if memories might have flashed through his mind.

We were going to meet someone he hadn’t seen in a long time. I was going to accompany him and document the reunion as part of my fieldwork.

A robotic female voice came over the Audi’s speakers. “Dead end ahead. Switching to manual mode.” A rockfall blocked the road in front of us.

The Audi iX disengaged the autopilot and switched to the manual mode.

Takehiko smiled as the mechanism roared. “I just love this moment.” Maybe there was something left for me to discover.

The lane on the side of the valley was barely wide enough for the car to pass through. Only half a century ago, a car could go through a road like this if the driver was a little bit cautious.

He stepped on the accelerator. There were about thirty centimeters of space between the rockfall and the vehicle.

The moment we slipped by, I saw the granite in the rubble through the passenger window. White mixed with gray made its presence shine, as if it were some sort of sign. Takehiko refused to turn the autopilot back on, perhaps because he felt encouraged after successfully maneuvering his way around the rockfall. “When I was young, there was no such thing as self-driving. Once I drove my then-girlfriend to the sea in our rental car, but my classmate came in his own car. It was a silver Jaguar. Ever since then, I’ve been fond of European cars. But now a framework such as Europe doesn’t really exist anymore.” He stepped on the gas with a little more force, and after we crossed the mountain pass, we began our descent down the serpentine slope.

Traces of past rockfalls littered the road, but fortunately they weren’t large enough to cause trouble. As the tree branches blocking our view thinned, a settlement in the middle of the basin came into view.

A geometrically shaped prairie that was a cultivated field spread like a patchwork quilt and surrounded concrete husks of long-abandoned houses.

“What’s the history behind this place?” Takehiko asked the digital assistant.

While the indicator icon rotated on the screen, the assistant rattled off tidbits in its electronic voice. “This is Uenohara City, Yamanashi Prefecture. Many ruins of the Jomon period have been found, but the Yayoi period saw it decline once. Then it was called Tsuru County, from the Heian period onward, but during the Warring States period, diplomatic incidents befell it, for it was a border town. When the Koshu Kaido was opened in the Edo period, it became a lively, bustling village with lodgings along the route. Notable areas include the Sagami River and the Yuzurihara district. Would you like me to describe these areas?”

“No thanks. What’s the peak population?”

“Some 30,000. The peak was reached in early 2000. It was designated as an administrative deregulation area in 2035, and subsequently, there has been no certified resident ever since.”

Takehiko guided the car along a crumbling asphalt road that ran through the village.

Only a few houses still stood, left in ruins, and all of them were made of concrete. A long time ago, the law had been amended so that wooden buildings deemed to be worthless would be demolished at the government’s discretion, but stone buildings fell outside the scope of the Vacancy Control Act.

Something about the concrete houses standing in the midst of grass evoked nostalgia. No wonder touring the ruined village was popular.

Before long, as we passed through a thick green area, we realized it used to be a Shinto shrine. Like stone buildings, religious institutions had also escaped demolition.

“Would you mind videotaping me?” He turned to me with a slight bow. Even though he was an atheist, he seemed to like the idea of visiting the old shrine.

Brushing the gravel and mud off my shoes, I stood by one of the pillars supporting the roof over the water trough and held the camera. Thanks to the auto-tracking mode, no special skill was required.

I should be able to capture good footage of him dropping change in the offering box. The clink of a coin landing on the others in the box added color to the solitude of stillness. Unlike Takehiko, I didn’t bring any change with me.

After a few rehearsals and the actual performance, Takehiko checked the footage. His posture was stiff. A human being in the presence of the gods must be more humble. There seemed to be some points of concern, but lack of perseverance, a characteristic of this age, seemed to have caught up on him.

“Well, it’s fine. I’ll publish it.”

When he tapped the share button, a beep signaled that the upload was complete. At the same time, something rustled behind us, and when we turned around, a skinny boy stood in the tall grass surrounding the shrine.

His skin was darkly suntanned, well beyond a healthy level. His clothes were outdated and worn but clean and in fairly good condition. It was rare to find a child in an administrative deregulation area. At least, children were less common than deer and boars.

“Which village are you from?” Takehiko asked.

The boy just uttered largely unintelligible words. Apparently, he was upset with us for shooting a video at the shrine. However, I wasn’t sure if he was for religious reasons or because we were outsiders invading their private sphere.

The boy’s words lacked any coherency, but he sounded like a mental patient bitterly complaining to his therapist. After we put away the camera, he finally settled down.

“This is the first time I’ve ever talked to an abandoned citizen,” Takehiko said. “We can hardly understand each other. I’m surprised.”

When I advised him to avoid using the derogatory term “abandoned citizen,” Takehiko shrugged. I hardly expected a seasoned business owner like him to make such potentially inflammatory comments.

“Excuse me. A choice of words can reveal true intentions. But it reminds me of the history of Europe. France, Germany, and Italy were once one country, weren’t they? Then it split into different countries, and after one century, their languages became mutually unintelligible. The same thing is happening in this country now.”

I thought of bringing up the latest hypothesis, but I checked myself. New research had debunked the old theory that the German, French, and Italian languages had diverged from each other in sixty years after the disintegration of the Frankish Kingdom. Rather, the drastic linguistic divergence was caused by the absence of a centralized media system and the adoption of peripheral dialects by the change of administration, and from a linguistic point of view, French and Italian were almost the same.

“But come to think of it, more time has elapsed since administrative deregulation than the years between the divergence of French and Italian,” I said.

He nodded.

It’d been nearly seven decades since the idea of administrative deregulation had been implemented. Depopulated areas with little prospect of recovery had been excluded from the administrative control area of the local government, and intensive mechanized monitoring had been employed to focus on reducing defense risks.

“I remember the good old days,” Takehiko muttered, grabbing the Audi’s wheel after settling in his seat again. “When I was young, my family and I stayed with our distant relatives in the Tohoku region for a couple of weeks. An old woman was there—she was younger than I am now. She was quite chatty, but I didn’t have the slightest idea what she was saying, just like that boy we met.” Takehiko tilted his head back toward the shrine that was growing smaller in the rearview mirror. “Even so, by the time I left the house, I was able to understand her. I suppose I got used to the way she talked. Human abilities work in mysterious ways.”

Before long, the car entered a mountain road again. The trees were thicker now, and the cool air seeped in through the ventilation system.

“But in that sense,” Takehiko said. “I should do the same as I did when I was a child, shouldn’t I?”

He continued to insist that regaining a common language over time wasn’t so difficult.

When he was young, that wasn’t outside the realm of possibility. Many people still spoke divergent dialects, and they succeeded socially while keeping their dialects. In particular, this was true in the Tohoku region when Takehiko was a child—especially in areas entirely designated for administrative deregulation. Even those who spoke incomprehensible languages talked about their lives, history, love, and justice in their own unique ways. The country still maintained a culture of respecting the languages of those people, even creating dictionaries for speakers of a certain language.

At the very least, we could have understood each other if we wanted to—Takehiko had grown up in a time when such simple beliefs were still alive.

***

Takehiko Nomi occupied an important position in some aspects of the history of his country. According to a statistical survey conducted by econometricist Yuki Kunieda, Takehiko’s accomplishments were fourth among the Japanese in the twenty-second century, although it wasn’t often mentioned. He had devoted his efforts to “blood transfusion for non-medical purposes,” “the sale of synthetic blood,” and “mass production of replacement organs,” and they were still considered three sacred treasures for humanity in the twenty-second century. They were so commonplace we hardly gave them any thought, but before those technologies were developed, people weren’t living their lives in the same way.

Takehiko Nomi was merely one of many players in the medical entrepreneurship boom flourishing in the 2020s. When he established his first company, people were deemed too old to start a business unless they were in their early twenties. Takehiko, then a financial planner who sold health insurance products for doctors, began to entertain a desire to start a business because he had a sports doctor named Tsugiharu Taka as a client.

Taka worked as a doctor at a university hospital, but he also ran a fitness gym on the side. The gym’s forte was its training regimen that actively incorporated blood transfusion, which was regarded as doping in professional sports at the time.

Takehiko was impressed with Taka’s vision that had led to the truth of body tissue replacement in an era dominated by magical techniques—dietary improvement and regular exercise—intended to manage nutrient control technology through changes in lifestyles.

Taka’s gym secured blood by purchasing it from the Maghreb region and Iran, but it had always weathered criticism in terms of management. At that time, excessive faith was placed in body tissues, and above all, beliefs about blood were deeply rooted.

Taka tirelessly sought recognition for his gym in the world of professional sports, and Takehiko positioned body replacement fitness as a health promotion facility and worked to obtain approval from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

Taka agreed to hand over thirty percent of the shares to Takehiko. Over the next decade, Taka and Takehiko navigated the ethically gray areas together as business partners, but their relationship came to an end with Taka’s heart attack. Taka didn’t go through blood transfusions, and in his own words, “naked as the day he was born,” he fell ill and died at the age of fifty-two. The fact that Taka, who was only slightly older than Takehiko, easily succumbed to one of the three major illnesses of that time vouched for the validity of his own medical theory: body tissue replacement was the most efficient anti-aging treatment for living beings, and it was the only thing worthwhile for humanity to get passionate about. On his deathbed, Taka transferred another twenty percent of the shares to Takehiko.

Over the next five years, his business steadily grew. An opportunity came his way when the Tikrit Conference was held in 2032. With Turkey and Iran as its leaders, the establishment of the Middle East Desert Conference had finally brought an end to the turmoil in the region, which had threatened to put world stability in jeopardy since the beginning of the twenty-first century. Also, thanks to the peace talks, it was revealed that the blood supply from Iran would go down in a short time, and the official supply would be reduced to one-thirtieth in three years. If nothing had been done, the project would have disappeared without a trace, but Takehiko succeeded in producing usable synthetic blood in such a short time.

According to the aforementioned Yuki Kunieda, synthetic blood was one of Takehiko’s most important achievements. In terms of scientific history, the idea of artificially producing the simplest blood with body tissue replacement technology supposedly had originated from Chinese scientist Xie Yongjiu. However, when Xie was in college, he worked part-time at the research facility managed by Takehiko. Four years before the Tikrit Conference, Takehiko had already entrusted the younger generation with the concept of synthetic blood. The synthetic blood created by Xie had been largely ignored by the scientific world due to the profane idea of generating and destroying a large amount of childish imitation of RNS, but the year before, sixty-seven years after its presentation, Xie was finally awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. He was the long-awaited one hundredth Nobel Prize winner in China.

Only nine years after the commercialization of synthetic blood, Takehiko’s health promotion facility Mortic founded Japan Organs as a new subsidiary. A photo in the press release triggered quite a stir with its sensational content. The picture showed a dimly lit factory where young men in white coats carefully examined reddish black organs immersed in fluid. While this image certainly made the viewer’s heart raced faster, hardly any opposition arose. By this time, in the 2060s, there were more people who had already benefited from body tissue replacement technology than those who hadn’t. Just as half a century ago, when people were excited about the advent of new machines, newly generated body tissues grabbed the public’s excitement. New organs finally spared people the fear of cancer. As a result, the life expectancy of seventeen developed countries had jumped to one hundred and twenty years of age. In fact, Takehiko was a living example. He would turn one hundred twenty this year. Thirty years earlier, his driver’s license would have been revoked.

***

The Audi iX traversed the lush green forest road, the sunbeams dancing through the trees and reflecting off its shiny red hood. Takehiko seemed to have already retreated behind his emotional walls. He had come to see his son.

Takehiko had dedicated much of his life to ensuring the vitality of his company, Mortic. As was the case with many forward-looking business leaders, he had neglected his family. He had faced a battle he had no choice but to fight, even if that meant he would have to cast everything aside. But a happy family had no use for such a struggle. Or rather, Haruka Nomi, his son, might not have been able to dismiss his father’s absence as only a busy father protecting his business.

Haruka was born when Takehiko was fifty, and he was his third son. At that time, Haruka was still considered as a “child born to an older father,” but Takehiko loved Haruka. It was virtually an open secret that Haruka was born out of wedlock, and his biological mother worked as a personal trainer at Takehiko’s gym. Takehiko had a strong conviction that a child should be born to a healthy mother, and his wife had no objection. The trainer, a former Olympic swimmer, had been selected by Takehiko on account of her fresh womb. For her trouble in taking on the role of mother several times, which was considered quite humiliating at that time, she was later appointed director of the gym.

Haruka left for England after elementary school and entered Eton College. He made excellent grades and possessed an incredibly long-limbed physique he had inherited from his mother. He was talented enough to repel contempt against Asians and had become a popular student, untouched by any prejudice. Above all, he charmed anyone who met him with his gentle almond eyes. At the age of seventeen, Haruka entered Massachusetts Institute of Technology, majoring in genetic biology. He was supposed to become an asset to his father’s business once he graduated.

After attending college for one year, Haruka decided to take time off and start his own business. It was an agronomy company, a little different from what Takehiko had in mind. Haruka turned down his father’s offer of financial help, and after raising six million dollars in venture capital funding, he launched a corporation that applied genetic engineering to large-scale agriculture. He was initially dismissed as a helpless David facing Goliath-sized conglomerates such as Nestlé and Japan Tobacco, but despite its initial struggles, his business expanded and increased its sales by employing strategies for attracting media attention, such as devising packages destined for refugee camps. Just two years later it was established, the company made its initial public offering, but to everyone’s surprise, Haruka, its founder, resigned from the management. He also dropped out of MIT and disappeared.

“It’s not that Haruka completely shut me out of his life,” Takehiko mumbled while he slumped in his seat, looking like he was falling asleep. Despite his one hundred and twenty years, he had maintained his youthful appearance. What could be called the shell of his soul seemed to be flaking off.

“Haruka had been practicing judo until he graduated from high school. Then he sustained herniated discs,” Takehiko said. “I had told him to use synthetic blood because he would have to replenish his nutrition after practice. But Haruka was stubborn for some reason. His condition had deteriorated to the point where he needed surgery. Although the surgery went well, he came up short afterward. When he was a junior, he only made the final four in the state tournament. When he moped over his defeat, I asked him, ‘‘Why didn’t you listen to me?’”

Takehiko crossed his arms in front of him and shut his eyes tight. The rubber tires hummed as they spun on the asphalt below the Audi.

“Haruka suddenly decided to quit school when he was twenty. He wanted to travel around the world as a volunteer,” Takehiko continued. “Back then it wasn’t uncommon for college students, so I okayed his decision. But he never came back. I did everything I could, I even contacted the US Embassy in Bangkok, but in the end I couldn’t find him. Until now. No, to tell the truth, I didn’t even try. He hasn’t come to see me for fifty years… so I guess there must have been some inconvenience… Oh, it’s an interval.”

Immediately after uttering the word “interval,” Takehiko suppressed a yawn and began to snore. Sleep Beat, a device for regulating sleep he had been developing, seemed to have activated.

I asked the digital assistant to calculate the difference between the estimated arrival time and Takehiko’s wake-up time. As the indicator icon began to spin, it answered that the difference was negative. I felt it was better that way. I shouldn’t be bothering Takehiko with many questions before his reunion with his son after fifty years of separation.

The Audi iX neared a pockmarked, paved forest road. We were supposed to be close to the commune Haruka Nomi had established. The settlement seemed to be located along a narrow path leading from the basin to the mountains of Shinshu. A bountiful supply of water enabled a good harvest of rice. An abandoned whiskey distillery’s spire peeped through the trees in the distance, resembling an old medieval castle. The distillery functioned as the main facility of the commune. Haruka Nomi had chosen to die in this verdant forest where time had stopped.

Takehiko showed no sign of waking up even after we parked in front of the distillery. His nap might have been his escape. His gentle snoring seemed louder once the engine shut off. Damp forest air oozed in through the air vents and made me shiver. I climbed out of the car and headed to the distillery’s entrance. On the façade, the name of Haruka’s commune— “Life Observation Corps”—was inscribed on a large wooden beam. Not particularly impressed, I shrugged. To each his own. He was born the son of a businessman who changed the world. Despite the fact that he had inherited his talent and status, he had thrown everything away. Such a man existed in this world.

“What’s going on?”

As I stood in front of the façade, a girl began talking to me. She seemed to be asking, “What do you need?” Her red sweatpants were like the old warning signs to stop or stay away. The girl’s gaze was vigilant, reflecting the thick emotional walls the commune had built over the last several decades.

“We’ve come to see Mr. Nomi.”

“Huh?” She cocked her head and narrowed her eyes, not seeming to understand me, before disappearing behind the façade. A while later, three young men emerged from the building. They asked me a lot of questions, seemingly quite apprehensive of my presence there. One of them, a young skinhead who appeared to be partly Latin American, had an unsheathed machete dangling from his waist. Intimidated by his glaring, dark eyes, I ended up disclosing Haruka Nomi’s father had come to see him.

“Hey, that’s a cause for celebration!” The young man with the machete hurried back inside. “I’ll fetch Grandpa.”

After a while, a rail-thin old man with long limbs appeared. The old man they called Grandpa was Haruka Nomi himself, and I was taken aback by his appearance: his saggy, liver-spotted arms peeking from beneath the sleeves of his T-shirt, his gray hair hidden under a simple straw hat, and, above all his deeply furrowed face. His dark eyes sunken under their droopy lids didn’t match the youthful look of the elder Nomi, the father. No matter what angle I looked at him, this old man only seemed like Takehiko Nomi’s father.

The old man’s face wrinkled into a smile as he took off his straw hat. “Welcome. I’m Haruka Nomi.”

“Hello, my name is Hajime Whitmore.”

Silence filled the air as I wondered if I should tell him I was there to interview him. Perhaps Takehiko should have been upfront about the purpose of our visit. While I vacillated, Takehiko had exited the car and was standing at a little distance. He slowly walked toward us and stood next to me.

“I’m Takehiko Nomi.”

Haruka’s expression remained unchanged. He seemed to have buried all his emotions in dark oblivion.

“Haruka, I’m your father,” Takehiko declared as if to confirm the validity of this statement, seemingly sharing my anxiety. No, his fears would have been much stronger than mine. When you face your son, who looks older than yourself, your belief that you’re the father can crumble easily.

“Yes, long time, no see.” Haruka lifted his straw hat, revealing his sweaty, thinning hair stuck to his scalp.

“I’ve come to apologize, Haruka.”

“Apologize?” asked Haruka, a smile forming on his face. “There’s no need. We’re family.”

As Haruka hid behind the mask of old age, I really didn’t know what he was feeling. Takehiko, on the other hand, was visibly flustered. He looked like he was on the verge of tears. He was being smothered by the weight of the void left over the fifty years that had flowed by him and his son.

“My grandson is digging his first well now. Why don’t you come with us? After all, he’s your great-grandson.” Haruka turned around and started walking. He moved with a limp, dragging his foot. He had reached his present age without his bad back ever healing properly.

We followed Haruka and went down a hill behind the distillery. Several people were waiting for him in a clearing below, and among them was a solemn-faced boy of about fifteen, sitting with a cylindrical tool. His white tank top revealed his boyish, underdeveloped shoulders and arms.

“Grandpa, let me get started.”

When Takehiko, still panting after climbing down the hill, crouched down, the boy stabbed the cylindrical tool in the ground. Then, as he started turning the spring winder at its end, the tip gradually dug into the soil, making cracking sounds as it scraped off dirt.

“Here boys must dig wells,” Haruka said. “That’s the first step toward adulthood.”

A while later, the boy stopped his hand on the winder and pulled out the central part of the tool, emptying the cylinder if the scraped-off soil. After he threw the dirt away, the boy began turning the winder again.

“How long does it take?” I asked.

“Let’s see. Maybe there aren’t any water veins here.” Haruka flashed a mischievous smile. “We can show them how to locate a water vein if they ask, but here they must hit water without asking. There’s water everywhere under the ground, so they can hit water if they dig at most three times. If they can’t dig, they can’t grow up.”

Takehiko, still silent, kept watching his great-grandson digging the ground.

“Why don’t you sit down, Father?” Haruka patted the ground next to him. “We have so much to catch up on.”

Urged by his son, Takehiko crouched down. They talked to each other, but I couldn’t make out what they said. I could ask Takehiko later how he felt and what he thought. Now, though, I had no intention of throwing cold water on their conversation as they tried to fill the void opened up over the last fifty years—most likely an impossible task. The two avoided meeting each other’s eyes and kept talking in a low, moderate tone. While Haruka wore a calm smile, Takehiko had a painful expression on his face, as if suppressing his emotion.

A couple of hours later, the boy pulled out the digging tool. The sun had begun to set, but there was still light enough to continue working.

“Grandpa, I won’t find it here, will I?” the boy asked Haruka.

“We don’t know yet. Keep digging, you may find it.”

“How much longer?”

“I don’t know. You may never find it.”

“What the heck!” The boy lay back on the ground and tried to catch his breath. Then he got up and resumed digging. His sweaty back was covered with mud, which turned white as it dried while he continued working.

When it became dark, they called it a day. After that, no one would watch over the boy while he worked. He would keep digging alone. He would also manage his own time. He would have to dedicate every spare moment—when he wasn’t studying or playing—to digging. When he succeeded in hitting water, the commune would hold a feast in his honor.

Takehiko and I turned down a dinner invitation and climbed into the Audi. Just before getting in, Takehiko exchanged a brief handshake with Haruka.

I had intended to use our three-hour return trip to Tokyo to interview Takehiko, but I couldn’t get much out of him. His features expressed deep agony, rather than the joy of the reunion.

“My son tells me to count what I love, because that’s all about me. Do you know what that means?” Takehiko asked me just before we parted ways.

“I don’t know,” I answered. Or rather, to be more precise, I took his son’s words at face value. There was nothing else to add. Why did Takehiko think he didn’t understand that? In the end, I didn’t get a chance to ask him.

Takehiko took his own life.

***

Takehiko Nomi had scheduled an email to be sent to me after his death. When he had learned Haruka had only a short time left to live in that brief reunion of father and son, he realized he should no longer be alive. It was quite a surprise that someone who had a groundbreaking impact on human life expectancy ended his own life for sentimental reasons, namely the old philosophy that a father shouldn’t outlive his son. The e-mail described all about his youth, such as struggles, regrets, deep sorrow, and a sense of helplessness. Here’s a quote from his last message: “Humans only grow as our roles change.”

This concludes my report on Takehiko Nomi. A man of his caliber may meet such an end. But I also feel there’s something more to it. Takehiko must have felt that his life had taken a wrong turn, and that he shouldn’t keep on living. A certain sense of purpose is embedded in humanity, but perhaps we haven’t yet overcome it.

*** *** ***

若者のすべて

私は能見武彦の運転するアウディiXに乗って、緑深い山道を進んでいた。赤く艶めいたボンネットの上を、木漏れ日が通り過ぎていく。武彦は少し濃いめに注文した季節外れのホットコーヒーをすすりながら、ゆっくりと目を閉じた。癖っ毛に覆われた彼の頭をヘッドレストが優しげに包む。おそらく、そのとき武彦の頭脳は、自分を待っている再会がどのようなものであるかについて思いを巡らせたことだろう。幾つもの回想が頭をよぎったはずだ。彼がいま再会しようとしている人との別れから、とても長い時間が流れていた。

やがてアウディiXは自動運転を停止し、マニュアルモードに切り替わった。

「私はこの瞬間が好きなんですよ」

武彦によれば、「この瞬間」とは、機械が音を上げる瞬間のことらしい。自分にも何かが残されているという、発見の気持ちがある。

——この先は行き止まりです。マニュアルモードに切り替えます。

アウディがそう言ったのは、なんのことはない、前方を落石が塞いでいるからだった。谷側の道路の幅は、なるほど、この車がギリギリ通れるかどうかというところだった。だが、ほんの半世紀前は、ちょっと慎重になるだけでこうした道をすり抜けられたものだ。武彦は静かにアクセルを踏み込んだ。二、三十センチは余裕がある。すれ違う瞬間、私の座る助手席から花崗岩質の表面がよく見えた。灰色の中に混じる白が、なにかの符丁であるかのようにその存在を輝かせた。たった数十センチ先で、と気を大きくしたのか、武彦は自動運転再開を断った。

「若い頃はまだ自動運転なんてなかったですからね。当時付き合ってた彼女とカーシェアして海に行ったら、同級生がマイカーで来た時があってね。銀色のジャガーでした。私のヨーロッパ車好きはそのときからですよ。もっとも、いまではヨーロッパなどという枠組み自体が意味をなしませんがね」

少し強めにアクセルを踏み、峠を越えると九十九折の下りに入った。何度か落石の跡があったが、幸い通れないほどではなかった。眼前を塞いでいた木々の枝々がまばらになるころ、盆地の真ん中に集落が見えてきた。とはいえ、もう廃墟になった場所だ。規則正しい草原のキルト織は、そこがかつて耕作地だったことを示していた。

ふと、武彦はアシスタントに尋ねた。

「この土地の歴史は?」

アシスタントはインジケーターをくるりと回しながら、語り始めた。

——この土地は山梨県上野原市です。縄文時代の遺跡が多く発見されていますが、弥生時代に入り、一度衰退します。その後、平安時代より都留郡と呼ばれましたが、戦国時代には国境の土地として外交問題が発生しました。江戸時代に甲州街道が開通すると宿が設置され賑わいました。特色のある地域は相模川、棡原地区です。これらの地域について説明しますか?

「いや、いい。最盛期の人口は?」

——約三万人です。二〇〇〇初頭に達成されました。二〇三五年に行政緩和区域に指定され、その後の定住認定者はいません。

武彦はそのまま集落の中を進んだ。何軒か朽ちたままの家が残っており、もれなくコンクリート製だった。もうだいぶ前、法改正によって、価値がないと見なされた木造建築物は行政の判断で取り壊されることに決まったのだが、石造建築物は打ち壊しの労から空家規制法の対象からはずれていた。草木の中にコンクリートの家屋が建っている光景には郷愁を誘うものがある。廃村巡りのツアーが人気だというのもうなずける話だった。

やがて、とりわけ緑の深い場所を通りかかると、そこがかつて神社だったことが見て取れた。石造建築物と同じく、宗教施設もまた取り壊しの難から逃れたのだった。

「ちょっとビデオを撮ってくれませんか」

武彦は私に向き直ると、恥ずかしそうに言った。彼は無心論者だったが、古びた神社に参るというアイデアが気に入ったらしかった。手水舎の柱に私が立ち、カメラを持った。フォロー撮影モードなので、とくに技術は必要ない。小銭などもちろん持っていなかったので、地面になかば埋まっていた玉砂利の泥を払い落とした。おそらく、賽銭箱に向かってお参りをするいい絵が取れるだろう。沈黙の侘しさに、賽銭箱の鳴る音が彩りを添えるだろう。

何度かリハーサルを終え、本番テイクが終わると、武彦は映像をチェックした。どうも、少し肩を張りすぎている。神事に赴く人間はもっと畏まっていなければならない。幾つか気になる点はあるようだったが、この時代特有の堪え性のなさが彼をもまた捉えたようだった。

「まあ、いいでしょう。公開します」

シェアボタンを押すと、アップロード完了を示すピキーンという音が鳴った。と同時に、私達の背後で物音がした。振り向くと、背後に立っていたのは痩せぎすの少年だった。肌はくろぐろと焼けており、健康的な度合いを通り過ぎていた。なにより、行政緩和地域に少年がいることは珍しい。少なくとも鹿や猪よりは。武彦は「君はどこの集落の子かな?」と興奮して話しかけた。だが、少年は聞き取りづらい言葉で返すだけだった。どうやら、神社で動画を取るという行為に対して怒っているようだ。それが宗教上の理由によるものなのか、それとも私たちが彼らの生活圏において部外者だからなのかはわからなかった。およそ、少年の言葉には論旨のようなものが存在せず、カウンセラーに恨みつらみを述べる精神病患者といった風だった。少年は散々言い募った末、私たちがカメラをしまうのを見届けてようやく安心したようだった。

「棄民と話したのははじめてですが」と、武彦は言った。「あそこまで言葉が通じなくなるものですね。驚きましたよ」

私が「棄民」という差別的な表現を改めるよう忠告すると、武彦は肩をすくめて見せた。彼のように訓練された経営者が火元になりそうな失言をすることは珍しい。

「失礼、本音は語彙に滲みますからね。しかしですね、ヨーロッパの歴史を思い出しますよ。フランス、ドイツとイタリアはもともと同じ国だったでしょう? それが分裂して一世紀も経つと言葉が通じなくなりました。それと同じことが、いまこの国では起こっているんです」

私は武彦に最新の研究仮説を伝えようとしたがやめた。最新の研究によれば、フランク王国分裂から六十年で独仏伊の言語が分かれたという説はくつがえされており、それよりも中央集権メディアの不在と政権交代による辺境方言の採用がドラスティックな言語分裂の要因であり、そもそもフランス語とイタリア語は言語学的観点からするとほとんど変わらない。

「しかしよく考えれば、フランス語とイタリア語がわかれるよりも長い時間は経っているわけですからね」

私がそう言うと、武彦は深く頷いてみせた。実際にそれよりも長い時間が経っていた。過疎化の進んだ見込みのない地域を自治体の行政管理区域から外し、徹底した機械化による監視によって国防上のリスク低減にのみ注力するという行政緩和のアイデアが実現してからもう七十年近くが経過していた。

「昔のことを思い出しまたよ」と、武彦は再び乗り込んだアウディのハンドルを握りながら呟いた。「私はまだ小さくて、東北に住む遠縁の親戚の家に家族で二週間ぐらい滞在したのです。そこには老いたお婆さんがいて——もっとも、いまの私より若いんですがね——なにか色々と話すのですが、まったく意味がわからないんですよ。ちょうどさっきの少年と同じです。ですがね、その家を去る頃にはもう話を聞き取れるようになっていたんですよ。耳が慣れたんでしょうね。人間の能力というのは不思議なものです」

武彦は盆地を横切るように運転しながら、幾つか補足した。言語の分裂という中世的状況や、対話による意思疎通性の向上、人類は時間を重ねてもあまり成長しないということ、ついには見捨てられた過疎地に好んで住み着く人々への共感などなど。いつしか車は盆地を抜け、再び林道に入った。先ほどよりも緑が深く、ひんやりとした山の冷気が換気装置越しに伝わってきた。

「でもまあそういう意味では」と武彦は呟いた。「私はこれから子供時代と同じようなことをすればいいのでしょうね」

時間をかけて共通言語を取り戻していくことはそれほど難しくないという主張を武彦は続けた。武彦が幼かった頃はそうしたことがないではなかった。強い方言を使う人は多くいたし、その方言を保ったまま社会的に成功する人も多くいた。特に武彦が子供だった頃の東北地方——いまでは地域全体が行政緩和指定された地域——などはとりわけそうだった。わけのわからぬ言葉を喋る人たちもまた、自分たちの生活や歴史や愛や正義について自分なりに語っていた。まだこの国にはそうした人々の言葉を尊重する文化があり、たとえばある言語の話者に共通の辞書が編まれもした。少なくとも、理解しようと思えばすることができる——武彦はそうした素朴な信念がまだ生き残っていた時代に育ったのだった。

*

能見武彦はこの国の歴史のある部分において重要な地位を占めている。あまり語られることはないが、計量経済学者国枝優希によってなされた統計調査によれば、武彦のなした業績は二十二世紀の日本人で四位である。彼が尽力した「医療目的以外の輸血」、「生成血液の販売」および「代替臓器の大量製造」は二十二世紀を迎えた人類にとっていまだ三種の神器となっている。あまりにも当たり前に普及しているので、我々は気付かないが、それらの技術が確立する前、人々はそのように生きていなかったのだ。

能見武彦は二〇二〇年代に隆盛を極めた医療起業ブームの駒の一つに過ぎなかった。彼がはじめての会社を作ったのは不惑を迎えた頃、二十代前半でなければ起業は遅すぎると言われた時代だった。医者向けの保険商品を販売するファイナンシャル・プランナーであった武彦は、高次晴というスポーツ医師を顧客に持ったことから、徐々に起業の志を持ち始めた。高は大学病院に所属する医師であったが、その副業としてフィットネスジムを経営していた。そのジムの売りは、当時のプロスポーツ界でドーピングとみなされていた輸血を積極的に取り入れたトレーニングだった。栄養素制御の技術を生活面から制御しようという呪術的な技術(食生活の改善・運動の習慣化)が跋扈していた時代において、体組織の置換という真理に到達した高の慧眼に武彦は関心した。高の経営するジムはマグレブ地方およびイランからの買い入れによって売血を確保したが、経営面では常に風評との戦いだった。当時は体組織に対する過剰な信仰があり、中でも血に関しての思い入れは強く根付いていた。高は自身の経営するスポーツジムをプロスポーツ界に認めさせることに執心していたが、武彦は体組織置換型のフィットネスを健康増進施設と位置づけ、厚生労働省の認可を得るよう働きかけた。推薦人を集めることのできなかった高は、武彦に株式の三十%を譲り渡すことに同意する。この後十年に渡り、高と武彦はともにグレーゾーンのビジネスを行う仲間として共に歩むのだが、その関係は高の心筋梗塞によって幕を閉じる。高は輸血を行わないまま、彼の言葉によれば「産まれたままの身一つ」のまま、五十二歳の若さで病に倒れた。武彦にとってわずかに年上だったにすぎない高が当時の三大疾病にたやすく捉えられたことは、自説の正しさを裏付けた。体組織の交換は生物にとってもっとも効率のよい延命治療であり、人類が唯一血眼になる価値がある、と。高は臨終間際、株式のさらに二十%を武彦に譲渡した。

それから五年に渡り、順調に事業を成長させていた武彦に契機が訪れた。二〇三二年に開催されたティクリート会議である。二十一世紀の幕開けから世界を不安に陥れていた中東の混乱は、トルコおよびイランを盟主とする中東砂漠会議の成立によってようやく幕を閉じた。この和平会談によって、イランからの血液供給量がわずかな間に減ることも明らかであり、事実三年の間に公式供給量は三十分の一になった。もしなにもしなければ事業は跡形もなく消え去っただろうが、武彦はこのわずかな間に生成血液を実用可能な段階まで仕上げていた。

生成血液は前述の国枝優希によれば、武彦のもっとも重要な功績の一つである。体組織置換技術においてもっとも簡素な血液を人工的に作るというアイデアは、科学史的にいえば中国の謝永久によってもたらされたことになっているが、より正確にいえば、大学生の頃に謝がアルバイトをしていたのが武彦の経営する研究施設だったのである。ティクリート会議の四年前から、武彦はすでに生成血液のアイデアを若者たちに託していたのだった。謝の作った生成血液ジェネリック・ブラッドはRNSの稚拙な模倣を大量に生成して破棄するという冒涜的アイデアによって学術的にはながらく無視されてきたが、発表から六十七年を経た一昨年、ついにノーベル医学賞を受賞した。中国にとって念願の百人目のノーベル賞受賞者であった。

生成血液の実用化からわずか九年後、武彦の経営する健康増進施設モーティックは新たな子会社として日本臓器を設立する。プレスリリースで発表された写真は、その扇情的なビジュアルでセンセーションを巻き起こした。薄暗い工場の中、液体に浸された赤黒い臓器が艶かしく光りながら白衣の青年達による入念なチェックを受けている。この写真は人々の心を確かにざわつかせたが、もう反対運動などは起きなかった。この時代、二〇六〇年代にはすでに体組織置換技術によって恩恵を得ている人の方が多かった。半世紀前の人々が新しい機械の出現に心を躍らせたように、この頃にはもう、新しい体組織こそが人々の心を躍らせたのだ。新しい臓器はついに人々を癌の恐怖から救った。これにより、先進一七カ国の平均寿命は百二十年に伸びた。事実、武彦はその生きる実例である。彼は今年、百二十歳になる。彼はほんの三十年前なら免許を取り上げられた年齢だ。

*

アウディiXはその艶めいた黒いボンネットに木漏れ日を映しながら、緑深い林道を進んだ。これまでは自動運転が挫折する瞬間を心待ちにしている風だった武彦は、もうすでに深い感情の襞へと入りこんでいるようだった。彼はいま息子に会いに来ていた。武彦はその生涯のほとんどを彼の会社モーティックの繁栄に捧げた。多くの先進的ビジネスマンがそうだったように、彼もまた家庭を蔑ろにした。すべてをかなぐり捨ててでも戦わなければいけない戦いが彼にはあり、幸せな家庭にとってそれは無用なものだった。いや、彼の息子である能見遥にとって、それは単なる家庭の不和ではなかったかもしれない。単に父親が忙しく、家庭を疎かにしたというだけではなかったろう。

遥は武彦が五〇歳の時に生まれた息子で、武彦にとっては三男にあたった。当時はまだ「遅い子供」という扱いになったが、武彦は遥を可愛がった。ほとんど公知の事実として、遥は不実の子であり、武彦が経営するフィットネス・ジムのトレーナーとの間にできた子供だった。かなり明確に、武彦は「子供は健康な母体から生まれるべきである」という信念を抱いており、彼の妻もそれを忌避しなかった。トレーナーである女性は、水泳のオリンピック候補になったことがあり、材料の新鮮さという観点から武彦に選ばれ、当時としてはかなり屈辱的だった複数の母Pregnantsの役割を引き受ける代償に、フィットネス・ジムの取締役となった。

遥は中学校の頃からイギリスに留学し、イートン・カレッジに入った。成績はすこぶる良好で、信じがたいほど手足の長かった母親譲りの体格を持っていた。アジア人に対する蔑みの目を十分にはねのけるだけの資質を持ち、あらゆる偏見から自由な人気者ジョックとなった。とりわけ、優しく目尻の下がった切れ長のアーモンドアイは、誰からも好かれるほど十分にチャーミングだった。遥は17歳でマサチューセッツ工科大学への飛び級を決めた。専攻は遺伝生物学——まさに父親の仕事の主力——になるはずだった。

大学へ一年通った後、遥は休学をしてビジネスを始めることになる。それは武彦の望んだような方向と少し異なり、遺伝農学だった。遥は父親の申し出を断り、ベンチャーキャピタルから六〇〇万ドルの出資を受けると、遺伝子工学を利用した大規模農業を行う会社を立ち上げた。当初はネスレやJTといったコングロマリットの前では無力と馬鹿にされたが、苦戦しつつもそれなりに拡大を見せ、難民キャンプに提供するパッケージの工夫など、メディアを魅了する手法で売り上げを拡大していった。そして、創業からわずか二年でIPOを果たすのだが、驚くべきことに創業者である遥は経営陣から退いた。そして、MITも退学して、姿を消すのである。

「遥からは明確に絶縁されたというわけではないんですがね」

と、武彦はアウディiXのシートに深く腰をかけながら、眠りにつくような表情で呟いた。一二〇歳という高齢でなお若々しさを保つ彼の魂の殻とでも呼ぶべきものがポロポロと剥がれ落ちていくようだった。

「遥は高校生の時分まで柔道をやっていたんですよ。それが、椎間板ヘルニアになりましてね。練習をしたらその分栄養を補給しなければいけないのだから、私は生成血液を使うよう勧めていたのです。しかし、遥はなぜか意固地でしてね。結局手術が必要になるほど悪化しました。手術は成功しましたが、その後の成績は芳しく無く、三年生の全米予選では州大会ベスト4という記録でした。私は敗北に打ちひしがれた彼を叱りました。なぜ親のいうことを聞かなかったのだ、とね」

武彦は腕組みをすると完全に目を瞑った。アウディのタイヤがアスファルトをなぜる静かな音だけが響いた。

「遥は二十歳のとき、突然休学を申し出たんですよ。ボランティアとして世界を回りたいと言って。当時はそれが大学生にとって普通のことでしたから、私は快諾しました。しかし、それっきり戻ってきませんでした。私はタイの米国大使館に連絡したり、色々と手をつくしましたが、結局はいまに至るまで見つけることはできませんでした。いや、正確には探そうともしませんでした。五〇年も会いに来なかったので……なにもなかったというわけではないのでしょう……ああ、インターバルだ」

「インターバル」という言葉を発した直後、武彦はあくびを噛み締め、寝息を立て始めた。彼がいま手がけている定期的な睡眠を管理する睡眠拍動スリープ・ビートがアクティブになったらしかった。

私はインジケーターに到着予定時刻と武彦の起床時間との差分を尋ねた。インジケーターはくるりと回ると、その時間がマイナスであることを告げた。私はその方が良いような気がしていた。武彦が五十年の時を経て息子と再会する前に、私があれこれ尋ねるべきではないような気がしたから。

アウティiXはところどころ禿げたアスファルトの林道に差し掛かった。このすぐ先に能見遥の築いたコミューンがあるはずだった。盆地から再び信州の山深い地域へと向かう隘路のような場所に集落はあるらしかった。利水がゆきとどき、よい米が作られる。打ち捨てられたウィスキーの蒸留所が、コミューンの中心的な施設となっている。遠くから蒸留所を眺めると、木々の間から覗く尖塔が古びた中世の城のように見えた。私も美しい緑の写真を見たことがある。時が止まった緑萌える美しい森で、能見遥はゆっくりと死のうとしていた。

蒸留所に停車してからも武彦が目を覚ます気配はなかった。あるいは、その惰眠が彼なりの逃避なのかもしれなかった。車内には武彦の寝息しか聞こえず、冷たく湿った森の空気がそっと私達を包んでいた。私は車を降りると、蒸留所の入り口へ向かった。ファサードには遥の作ったコミューンの名称「人生観測隊」が大きな枕木に刻まれていた。人の生き方はそれぞれだな、と私は月並みな感想を抱いた。世界を変えたといっていい実業家の息子として生まれ、また自信もその才能と地位を受け継いでいたにも関わらず、それを全て捨ててしまうような人間がこの世には存在するのだ。

「なんかした?」

ファサードの前で立っていた私に少女が話しかけてきた。「なにか要ですか」と訪ねているのだろう。赤いスウェットに身を包んだ彼女が向ける自警的な眼差しは、このコミューンがこれまで永らえてきた数十年に築いた心理的城壁の硬さそのものだった。

「能見さんという方に会いに来たのです」

少女は「ハア?」と苛立ち混じりの声を上げるとファサードの奥に消えていった。ほどなくして、ファサードの奥から三人の青年が現れた。青年たちは私の目的についてかなり警戒しているらしく、色々と問いただした。おそらく南米の血が混じっているらしいスキンヘッドの青年は腰に山刀マチェーテをぶら下げていた。結局、私はその青年の暗い目の輝きに怯え、正直に能見遥の父が彼に会いに来たことを暴露してしまった。

「へぇ、それはめでたい!」

マチェーテの青年はそう叫ぶと、すぐに「ジージ呼んでこよう」と走り去った。しばらく経つと、ファサードの奥から痩せ細った手足の長い老人が姿を表した。ジージと呼ばれたその老人こそが能見遥であり、その姿は私に強い違和感を覚えさせた。Tシャツの裾から覗く筋肉の落ちたしみだらけの腕、麦わら帽子の下に隠れた白髪、そして何よりも深い皺の刻まれた顔。たるんだまぶたの下に落ち窪んだように見える暗い瞳は、父である能見武彦の若々しい表情と符合しなかった。どう控えめに考えても、こちらの老人こそが能見武彦の父であるとしか思えなかった。

「ようこそいらっしゃいました。能見遥です」

遥は麦わら帽子を脱ぐと、ほほ笑みを浮かべた。

「はじめまして。ハジメ・ウィットモアと申します」

しばし沈黙が続いたが、私は今回が取材であることを正直に言っていいのかどうか悩み続けていた。それよりもまず、武彦が自分から言うべきではなかったか。その逡巡のうちに、私は背後に武彦が立っているのを認めた。眠りから目覚めたらしかった。武彦はゆっくりとこちらに歩み寄ると、私の隣に立ち「能見武彦です」と告げた。遥の表情は微動だにしなかった。老いの暗闇の中へ感情のすべてを押し殺してしまったように私には見えた。

「遥、父さんだ」

武彦もまた、私と同様の不安を抱えたのだろう、確認するかのように宣言した。いや、彼の不安は私よりもずっと強かっただろう。自分よりもずっと年老いた息子を前にしてしまったら、自分が父親なのだという信念は容易に揺らぐ。

「はい、お久しぶりです」

遥はそう答えると、麦わら帽子をさっと上げた。薄くなった頭髪が汗で張り付き地肌が見えていた。

「お前に謝りたくて、来たんだ」

再び武彦が言った。遥は「謝る?」と問い返した後、ふっと微笑みを浮かべた。

「そんな必要はないですよ。私たちは親子ですから」

再び表情を老いのベールに隠してしまった遥の言葉からは、どんな感情も読み取れなかった。武彦は明らかに狼狽していた。泣き出しそうにも見えた。父子の間に流れた空白の五十年がその重みで武彦を窒息させようとしていた。

「いまから孫が初めて井戸を掘るんです。よかったら見に来ませんか。あなたにとっても曾孫ひまごですし」

そう言うと、遥は振り返って歩き出した。足を引きずった歩き方で、おそらく彼は腰が悪いままこの歳を迎えたのだった。

私達は遥について蒸留所の裏手にある丘を下った。一段低くなった土地には何人かが遥待っており、その中の一人、十五歳ぐらいの少年が筒状の器具を持って神妙な面持ちで座っていた。白いタンクトップで、そこから覗く腕は少年らしく頼りない筋肉で覆われていた。

「ジージ、やるぜ」

丘を降りて喘いでいた武彦がしゃがみ込むと、少年が持っていた筒状の器具を地面に刺した。そして、尻尾の部分にあるゼンマイ式のハンドルを回し始めると、先端が少しずつ地面にめり込んでいく。カリカリと土を削ぐ音がする。

「ここでは、こうやって井戸を掘るようにしてるんですよ」と、遥が言った。「それが大人の第一歩ということです」

しばらくすると、少年はハンドルを巻く手を止め、器具の中央部分を引き抜くようにした。すると、削られた土がドサッと出てくる。土を捨てると、少年は再びハンドルを回した。

「どれぐらいで掘れるんですか」

私が尋ねると、遥は「さあ、もしかしたら水脈はないかもしれんしね」とこともなげに答え、いたずらっぽく笑った。

「水脈の見つけ方なんて、聞けばわかるんだが、聞かんようにして掘り当てるのがここの流儀なんですわ。まあ、そこらじゅう地下水通ってますから、多くても三回掘れば当たりますよ。掘れんかったら大人になれんということです」

武彦は相変わらず黙ったまま、曾孫の井戸掘りを眺めていた。

「父さんも、よかったら座りませんか。積もる話もありますし」

武彦は息子に促される形で隣にしゃがみこんだ。なにかを話しているらしかったが、私からは聞こえなかった。武彦がなにを感じ、何を思ったのかは、後から彼に尋ねればよかった。いまはただ、五十年の空白を埋める会話——もしかしたらそんなものは不可能なのかもしれないが——に水を差すつもりはなかった。二人は視線を合わせず、控えめな会話を続けていた。遥は穏やかに微笑を浮かべ、武彦は感情を抑えるような苦しげな顔をしていた。

二時間ほど経った頃、少年は井戸掘り器を引き抜いた。日が少し傾き始めていたが、まだ作業は続けられるほどには十分明るかった。

「ジージ、ここ、出ないじゃろ」

少年は遥に尋ねた。

「まだわからんぞ。出るかもしれん」

「あとどんだけ?」

「知らん。出ないかも知らん」

「なんじゃーもー」

少年は地面にひっくり返った。そして、仰向けのまま息を整えると、再び立ち上がって井戸掘りを再開した。濡れた背中にはびっしりと泥がついたが、作業を続けるうちに白く乾いていった。

そのまま暗くなり、その日の作業は終了となった。これ以降、少年の井戸掘りが見守られることはない。彼はたった一人で井戸を掘り続ける。時間の工面も自分で行う。勉学の合間や遊びの誘惑など、生きる上で訪れるすべての合間を縫って井戸を掘り続け、見事掘り当てた時に祝宴が開かれるそうだった。

武彦と私は夕飯の誘いを辞し、再びアウディに乗り込んだ。車に乗る直前、武彦と遥は短い握手を交わした。

東京に戻るまでの三時間を私はインタビューにあてるつもりだったが、聞き出せたことは多くなかった。武彦の顔に浮かんでいるのは、再会の喜びというより、深い苦悶だった。

「あいつがね、言うんですよ。愛しているものを数えてくださいって、それがあなたのすべてですって。どういう意味か、わかります?」

別れ際、武彦は私に尋ねた。私は「わからない」と答えた。いや、正確にはそのままの意味だと思ったのだ。そこに付け加えるべき言葉は何もなかった。武彦はなぜ、それをわからないと思ったのだろうか。結局、その答えを聞く機会は訪れなかった。武彦が自ら命を断ったからだ。

*

能見武彦は私に死後予約送信のメールを残している。あの短い父子の再会の中で、遥の余生が残り少ないことを知った彼は、もう自分が生きているべきではないと悟ったそうだ。人類の寿命というものに対して画期的な行いをした彼が、「親が死に子が死に」といったレベルの感傷で命を断ったという事実は、驚くべきことだ。そのメールには葛藤や後悔、深い悲しみ、無力感といった、若者のすべてが書いてあった。その一節を引用する。

人は役割の変化でしか成長しない

以上で、能見武彦に関する報告を終わる。偉大なる一人物の最後はこのようなものであるのかもしれない。だが、それとはまた別の何かが存在しているような気もする。武彦が自分の人生を間違っていると感じたであろうこと、そして、自分がもう生きていてはいけないと感じたであろうこと。単なる自己処罰感情とは異なる、ある種の目的意識のようなものが人類には存在しており、私たちはそれを克服していないのではないだろうか。

Fumiki Takahashi is an award-winning Japanese author, born in 1979 in Chiba. While still a student at the University of Tokyo, he made his literary debut in 2001 with the novel Tochugesha. Since 2007, he has edited the literary journal Hametuha. Authors he admires include Kenzaburo Oe, Michel Houellebecq, and Gabriel García Márquez. Translations of his short stories have appeared or are forthcoming in venues such as Another Chicago Magazine, Bewildering Stories, Eckleburg Review, Gargoyle Magazine, and Mount Hope.

Fumiki Takahashi is an award-winning Japanese author, born in 1979 in Chiba. While still a student at the University of Tokyo, he made his literary debut in 2001 with the novel Tochugesha. Since 2007, he has edited the literary journal Hametuha. Authors he admires include Kenzaburo Oe, Michel Houellebecq, and Gabriel García Márquez. Translations of his short stories have appeared or are forthcoming in venues such as Another Chicago Magazine, Bewildering Stories, Eckleburg Review, Gargoyle Magazine, and Mount Hope.

Toshiya Kamei holds an MFA in Literary Translation from the University of Arkansas. His translations of Latin American literature include books by Claudia Apablaza, Carlos Bortoni, and Selfa Chew.

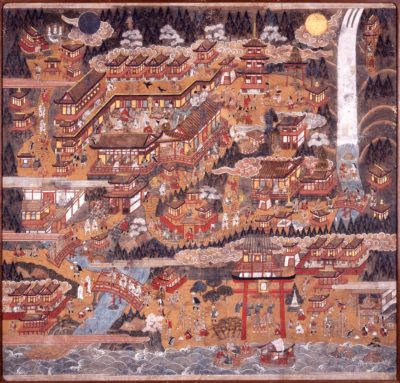

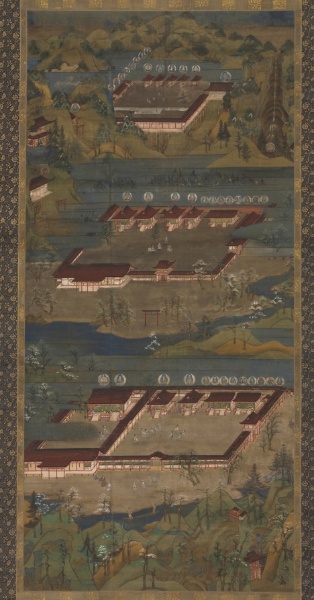

Artwork (in order of appearance):

Nachi Sankei Mandara

https://www.univie.ac.at/rel_jap/k/index.php?title=Kumano_mandara&oldid=15397#/media/File:Nachi_sankei_mandara.jpg

Kumano Kanshin Jikkai Mandala, early Edo period

https://www.hyogo-c.ed.jp/~rekihaku-bo/historystation/digital-exhibitions/maya/obj/img/item01_mainimg.jpg

Kumano Mandara

https://www.univie.ac.at/rel_jap/k/index.php?title=Kumano_mandara&oldid=15397#/media/File:Kumano_Mandala.jpg

Kumano Kanshin Jikkai Mandala, early Edo period

https://www.hyogo-c.ed.jp/~rekihaku-bo/historystation/digital-exhibitions/maya/obj/img/item01_tex2-2_img.jpg