Ripe Fruit by Katie Mitchell

I am seated on the hard chair in the therapist’s office with my then-husband to my left. The therapist leans back against his own chair, relaxed, taking notes. My husband leans back comfortably as well. I fidget incessantly from the left to the right, twisting my wedding rings around my finger repeatedly while he speaks loudly and clearly with ease. It is our first appointment, and we discuss the affair I know he is having. But in this office, it is not an affair. Platonic friendship is the chosen narrative here. I cry when I explain why I cannot swallow that story. My body knows it’s not true. I haven’t slept in weeks. My bones rattle and my stomach turns; it feels like tiny earthquakes inside. But the certainty cannot reach my mouth. It stays trapped in my belly, and my anger is contained in my chest where it has turned into sorrow instead. My voice sounds shaky, pathetic. The clock on the wall ticks against the silence that hangs in between our attempts at conversation.

As the session concludes and we have gotten nowhere beyond my tears and his denial, the therapist tells us maybe for this week, just try to be nice to each other. “Treat each other like you would treat a coworker,” he says in his distant, professional voice. “Be courteous. Give the benefit of the doubt.” Then he adds that we could perhaps think back to the very beginning and consider better times with each other and what drew us together.

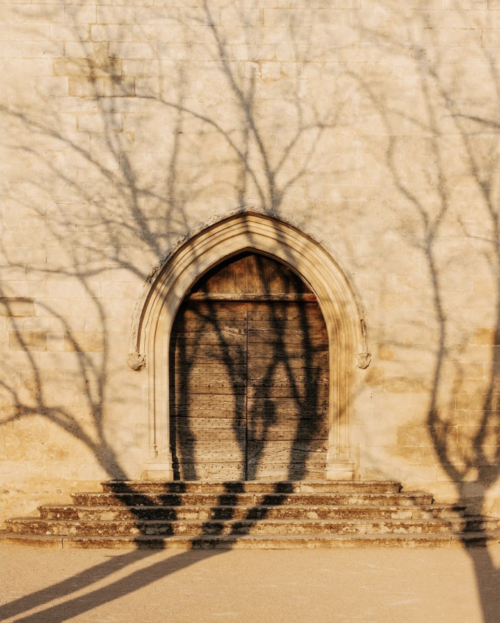

That night, we return home after a tense dinner out where I shift my salad around with a fork and trace my finger around the rim of the wine glass, avoiding my husband’s glare across the table. I lock the door of the guest bedroom and try to sleep there, but he picks the lock and enters. It is his house, too, but he doesn’t ask permission before he opens the door to the room of my own.

I follow the therapist’s advice and try to remember the very beginning. I close my eyes to see the night we met. I was a wallflower at a college party in a dusty apartment, but I said yes when he asked me to dance in the cramped living room and felt chosen when he kissed me. I think back to our marriage proposal five years after that. I remember the black dress I wore; one I’d bought at a consignment store on my graduate student budget. I remember the nerves in my stomach as I reached my hands behind my shoulders to zip it up the back then curled my hair, glancing in the mirror inside my small, sparse apartment. My roommate snapped a photograph as a limousine picked us up. My smile was tense, and I knew a surprise of some kind was in store that night. I hate surprises.

I remember my hip sliding sideways into the long leather seat when the limo arrived, carefully folding one leg in the car and then the other, like a lady. We were heading to an iconic city park to stroll before a museum visit, but he asked the actual question in the back of the limo where we were alone together, riding to what was, to me, an unknown location across the city through narrow streets and tall buildings. He pulled out a black velvet box with a shiny ring, and then he slipped it on my bony finger. It felt unfamiliar on my hand. I remember walking the park together then riding across town to see an Impressionist exhibit at the art museum, my diamond glinting in each room under the piercing museum lights, my heels clicking on the shiny hardwood floors, and swirls of color on every canvas. We ate dinner at the Ritz Carlton and slept there that night. The bed felt like more luxury than anything I’d known before, sheets cool and heavy against my skin. The next morning, we rode the elevator down to the parking deck, and I caught my reflection in the gold, mirrored sliding doors, the ring glinting back at me. I remember all of these details, but I cannot remember saying yes. I’m sure I did. I must have. But I cannot remember the moment I actually uttered that word.

When I look for synonyms for the word yes, I find affirmative, certainly, without a doubt, undoubtedly, unquestioningly.

************

When I was in the fourth grade, Clarence Thomas had his senate hearings. I remember sitting in the living room at my grandparents’ house with the hearings on the television and all the adults in the room hovering around like bees, talking about it. My ten-year-old ears were listening and threading the bits and pieces into context as I observed the way adults say something without actually saying it.

I gathered that a woman had a story, and that story was somehow false. She said a man did something inappropriate, but she had to be lying. He was distinguished, a judge, a conservative, not the kind of man to do that. Years later, she had dinner with him again, after all. She never shouted loudly that her answer was no. She never denied his advances at the time, but later she complained about them.

We all ate dinner together, and then the kids played in the room, weaving in and out of adults standing and chattering near the humming television. By the end of the night, I understood who Anita Hill was. I knew that the absence of a loud and defiant refusal in the moment served as her assumed permission, and now everyone knew she was a liar. This was a concrete fact, the way the world worked. A loud refusal was the only no.

In Sunday School we learned about Eve who ruined it all with her appetite, her wanting, her reaching for the ripe fruit. I imagine Eden, what it must have felt like, naked skin without shame in the sunlight. Surely that first bite was soft to the touch. Eve’s long arm reached upward among the leaves, alone with the exception of the serpent and his shimmering scales. She grabbed the roundest and fullest fruit she could find, inhaling the scent on the skin, piercing the flesh with her teeth. Look at what happened when a woman chased her own desire for sweetness and satiated her hunger: the whole world fell to pieces and came off its careful hinges.

We learned about male desire, too. King David with his eight wives saw Bathsheba bathing in the moonlight, water glistening on every curve. He wanted her so badly in that moment that he called her to him, this powerful king and his beautiful subject. He had her because he wanted her, and she eventually gave him the child he wanted––his heir to the throne. She was his prize two times over, first in body and then in lineage. No permission needed or granted, no moment in that story to talk about Bathsheba and what she wanted. Thousands of years later, and we know her by her beauty, her irresistible body whose power didn’t even belong to her. Why was she bathing in the moonlight, this temptress? Her glistening curves glowing so brightly that her siren’s song traveled all the way to the palace where even strong David couldn’t help but call for her. She was chosen, beckoned, held, consumed.

************

My first boyfriend happened when I was 14. He was 17. His mother had a loud laugh and a lot of jewelry. His house felt different from mine: more noise, fewer rules, not much supervision. He kissed me, and then we were together. From what I could gather, that simply meant I belonged to him somehow, our longings tied together, my desires now his. I don’t remember a distinct moment of choice. We morphed into this shape together, and I felt chosen. We spent weekends on his couch watching movies he wanted to see. Me watching him, gazing through his eyes to the screen in front of us.

But eventually that cage became itchy and confined. Belonging felt heavy. Months later, he was driving along the road in his car with me in the passenger seat, and I waited until we passed a particular house to tell him that I wanted to break up. I knew that house with its Christmas lights on in January. I’d noticed it as a landmark and timed it on our previous drive. I knew it allowed only ten minutes together before arriving at my doorstep, so the discomfort wouldn’t last too long. I carefully planned the conversation to hopefully make it less uncomfortable for both of us. Softening the blow, accommodating him as best I could, even in my attempt to break away. I was fourteen, not old enough to drive or to know much of anything about how the world worked, but I already knew how to make myself smaller, quieter, quicker, how to make things easier for a man. How to make a nearly silent exit out the side door. Maybe every man in my life has tumbled out of that first doorway.

Two years later, I had another boyfriend. We had a definite beginning. I watched him from the margins of his life and wanted him long before we were together, and then one night he asked for help with his French homework and we ended up in the backseat of his car. I wore a purple sweater, and I still remember the way he smelled and how I wanted to inhale every piece of him and fold myself up to stay in the hollow of his collarbone.

For the first time in my life, I felt that desire with certainty, without a doubt, unquestioningly. When I was with him, my own desire felt like a river that smothered all of the questions that hummed inside. For months, we fumbled with the earliest beginnings of what it was like to explore another’s body. Though everything in me wanted to say yes, I said no. I built a dam to contain the river. I knew the punishment of Eve, the warnings I’d heard about what happens when I let my desires propel me. I stayed in line to follow commandments that were not my own, and I swallowed them as truth.

Perhaps they are the same: silently permitting when you want to say no and saying no when, deep inside you, there is a yes wanting to make its way to your mouth. Now I see what I didn’t know then––that yes lives in the body and no lives there, too.

That same year, the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal was all over the news. I was older this time, but I still heard adults buzzing around me discussing events as they unfolded. While they were unbothered by the Clarence Thomas accusations seven years earlier, my conservative family was on fire about this. I didn’t fully understand why Thomas was guiltless and Clinton was loathsome except that details of the body were present this time. Discussions I overheard: cigars and semen and a stained blue dress; how despicable a man was who would do these things; how she must have been after something. Words I never heard: power and consent. When my boyfriend and I were fumbling that year in the back seat of his car, all of my yesses became a no because I saw my power as outside myself, as some force that could only be granted to me from some other place. My life could not have seemed farther from Lewinsky’s, but perhaps there was a thread there between us. Perhaps she could not hear herself above the power of someone else’s ambitions, and I could not hear myself apart from the shapeless form of some force outside me that held the keys to my own body.

************

In eleventh grade, I entered a pageant called a scholarship competition, a longstanding tradition in my hometown. Girls posing in a row with numbers pinned on our modest evening gowns, chosen carefully by our mothers. A fitness routine we learned together, a talent showcase, and earlier that day, a long interview with a panel of women in someone’s living room with freshly vacuumed carpets, heavy draperies, and lemon squares on a platter for the judges.

I won the fitness portion, my strong dancer legs kicked higher than everyone else’s in the routine and my years of ballet training taught me to keep a solid back, squared shoulders, and a smile on my face no matter how nervous I was on the stage. At the end, we stood in lines with our numbers pinned and our smiles wide. Waiting to be chosen. A bouquet of flowers was handed to each girl when she won something, but the biggest bouquet was for the winner. So heavy she could barely carry it out the backdoor of the auditorium when the night was over. When you are chosen, the burden and the prize are one and the same.

************

Five years before the stiff chair in the therapist’s office, I was forty-weeks pregnant with my son when I went in for my weekly obstetrician visit. There was no sign of labor anytime soon. My usual doctor was out with an of injury, the office staff explained. He’d twisted an ankle on a shift at the hospital. I waddled in, swollen and tired. I’d done anything I could imagine trying and get this baby out––walking my steep driveway repeatedly every day, eating spicy food and baked eggplant, having awkward sex beneath my beached whale belly to try and activate prostaglandins. Nothing worked, and I grew frustrated with my body that felt broken and unresponsive.

A doctor I’d never met before came into the room. He was old with gray hair and reading glasses he peered through while flipping through my chart with pursed lips. Explaining the need for the baby to come out soon but also assuring me all was fine, he motioned for me to pull my pelvis down to the bottom of the table for the routine cervical check to take a look at my dilation. I shimmied my round shape down as best I could and opened my legs wide, feeling the warmth of the spotlight lamp. He shoved his gloved hand higher and higher still until I felt like I’d be pushed back out the door of the exam room. He mumbled something about my one centimeter dilation and said, “I can help you out if that’s alright?” I didn’t know precisely what that meant, and his gloved fingers were far so inside me I could hardly speak, so I simply mumbled okay in a pinched breath, ready for whatever was happening to be over. Before I could exhale, I felt a searing pull I didn’t remember in these checks before, and it made me sharply inhale again and catch my breath. As quickly as it started, it was over. He removed his hand and told me I could sit up.

Hoisting myself up on my elbows and then all the way up, I closed my legs and placed the paper apron over my thighs as he threw his latex glove in the trash. “I helped nature along a little bit,” he said with a wink. “You are hardly a centimeter dilated, so I stripped your membranes. That should hurry the baby along.” He grabbed my file and walked out the door. In the office, with my paper apron over my lap and no full understanding of what had just happened, I could only flatly mutter “thank you” as he left. I dressed myself and drove home, trying to keep my anger sealed somewhere it couldn’t escape. When I got home, I opened my pregnancy book to see that stripping the membranes meant his gloved finger separated the amniotic sac from the wall of my uterus and cervix.

Even my anatomy granted permission without saying yes. Soft pink folds that stood as a doorway to my interior, but he didn’t even have to pick the lock to get in without asking me. My exhausted face and bulging belly, my back flat on the exam table, my implied permission.

************

Two years after the stale therapist’s office, divorced with a house of my own where no one else could unlock the doors, I found myself at a corner table with a man who had eyes the color of the far end of the ocean. The way he looked at me disarmed me, made me feel unsteady and powerful at the same time. He was tall and thin and had a stride twice the length of mine and a voracious interest in me that he hardly attempted to hide, a hunger for every word that came out of my mouth, every detail. That first night, we snacked on chips and sipped icy margaritas like it was summertime, even though it was three days before Christmas. The wind outside was chilly and there were twinkling lights along the window of the restaurant, and he walked me to the car in the dark. We kissed longer than I thought we would, his hand tight at my waist and my back against the car door, margarita salt on our lips. He didn’t ask before he kissed me, but I suppose there were ways I granted permission for that: eye contact lasting longer than usual, a small lean inward to him. Whatever the clues, he kissed without asking, and I kissed him back.

The next day, he texted to say he bought tickets to The Nutcracker, and we found ourselves in the dim light of an old theatre watching dancers twirl. He came back to my place, and perhaps for the first time since I was 17 in the back seat of my boyfriend’s car, I said yes to something. Certainly, undoubtedly, unquestioningly. I closed my eyes and submerged myself into the flowing river of my own longing without fear of what was on the other side.

There is a numbness when you cannot hear the clarity of your own desire. And there is a power in the word no. It tastes sharp; it is loud and quick and assertive, solid as a stone. But yes, has a power of its own, and that night felt like water, warm and flowing. A river flows its way to freedom and changes rocks and landscapes. Its current carries a branch somewhere far away without knowing exactly where it will land, and that night I was carried across the threshold of my own locked door to a place where I was all longing, wanting, devouring, pursuing.

But then the next week on the phone, his cheerful voice called and teasingly asked, “So when will you relax into this relationship?” And there it was again, the feeling of being chosen, picked, receiving instead of chasing. No longer in the driver’s seat, somehow here again, carved from where I was to take the shape he wanted. The word relationship echoed heavily in my head a few times after we hung up, but then I remembered this is what all the books tell us is the best sign, a unicorn, a man ready to commit. The prize. Never mind the choosing, just be the chosen. No yes required. Don’t make him pick the lock; just silently open the door.

Eventually, it cracked. I knew all his preferences for television shows, his favorite meals, his schedule. He couldn’t remember how I liked my coffee and nearly died of boredom when I dragged him to a production of As You Like It and we drove home with his annoyed sighs and my incessant chatter about the characters. Fifteen months after that first date, he was crying in my kitchen, tilting his face so that I could not see. I told him, “I cannot do this anymore. It feels like I have set myself on fire to keep someone else warm.” It was there again, my refusal to belong to someone.

My quiet exit out the side door did not work this time. I burned it all down instead.

************

The last man who walked the landscape of my body was tall and bearded with black hair and clear blue eyes. He wore glasses and read books and recognized I had a brain. Our first few dates were an endless stream of conversation, gliding from one topic to the next with ease. We hiked to the top of a local summit, and he was breathing hard from the incline. I wasn’t. I made a casual comment about what a steep climb it was so I could ease the moment and put us on equal footing, making myself a little smaller.

On our third date, when it was time for him to leave, his hands were on my hips before I knew what was happening. While I mirrored him, I tried to listen for that yes or no deep inside me where it lives. I couldn’t hear it, only silence. I kept waiting for a yes to speak to me from some cavern inside, waiting for desire to turn on like an engine. We fumbled with one another, not finding the same tempo. Half an hour later, as I laid beneath him on my couch, his heaviness on my body, it was still silent inside. I didn’t want to say no, but I knew it wasn’t a yes. I kept going anyway. I looked at him and could see the desire in his face, his hands roaming hungrily. But beneath that, in my own body, there was a numbness I stepped over to fill the space he held for me. It felt like there was some room deep inside me where certainty lives, and perhaps I was born with the key, but after a lifetime of stories that told me my power lives elsewhere, I don’t have it anymore

He knew nothing of keys and power and locked doors and cavernous echoes. All he could hear was the soundtrack of his wanting.

I wanted to feel the river again, the one that carries me to that place of my own longing, and for seven months I tried to find that current. There was no ripe fruit waiting for me to taste it, but I ate the unripe fruit instead and called it good, never admitting its sourness to him or even to myself.

He arrived at the doorway of his own desire every time. I never did.

************

The script tells me that men chase. They pursue, they decide. Women acquiesce and permit and enfold. There is some whisper deep inside my own body, but often when I am searching to find it, I cannot hear a thing. I have spent a lifetime learning how to ignore it. I have said yes when I meant no. I have said no when I desperately wanted to say yes. And sometimes I have said nothing at all when I tried to reach into the well of my body to feel what she wanted and the echo felt so far away that I could not get to the bottom of it. I have felt my body’s presence as a power and a burden, as an apology and a manifesto. I am still learning. I am unlearning. I have fumbled with someone else’s body trying to hear the voice of my own in the narrow space between us. I have opened my door silently, and I have hidden inside when someone else picked the lock. I run my hands along the wall of my own longing, feeling for a light switch, looking for rooms no one has entered before, not even myself, searching for affirmative, certainly, without a doubt, undoubtedly, unquestioningly.

Katie Mitchell is an English teacher who lives in suburban Atlanta with her two children. Her work has previously appeared in Yellow Arrow Journal, The Appalachian Review, HerStry, Braided Way Magazine, and The Manifest Station, among others. She is endlessly curious about the ways the natural world mirrors our internal landscape and the intersection of the cultural and the deeply personal. A seventh generation southerner, she is currently at work on a memoir about grief for both people and places that are long gone.

Jovani Demetrie is a Mexican-American photographer based in Brooklyn, New York. His clear, clean style captures beauty and realism in equal measure and extends to subjects both still and full of life. As a travel photographer, he has photographed (and happily eaten his way through) over 70 countries on 6 continents. As a portrait photographer, he has photographed over 1,000 artists in New York City.