What is Special About Dusk

photo collection of the author

by Katiy Heath

A cloud would soon billow out, a considerable mass, smoky red; a disorientating blanket of color, devilish red, divine red, nuclear and unnatural. Yet nature is what would send red into our tender hearts on the afternoon of this annular eclipse. From the Latin word annulus, meaning little ring. Like a hula hoop, a donut, a CD. A little band of light left after the moon moves across the sun, obstructing all but a six percent sliver. Little—130 miles wide—ring of fire that we didn’t have to put ourselves in the path of, it would come to us, enclose our little lives in a brief, beguiling black haze dark enough to signal God was in our midst.

Most of my childhood God spoke through wreckage. Tin sheds flung into the street; roofs popped off our porches with ease like the reassembling of a dollhouse. When a storm laid a tree to rest on top of my parents’ Ford Contour, God was speaking to us. Each time our basement filled with river water, God had something to say. Every lightning bolt or gust of wind was a sweeping piece of language, a declaration from the holy spirit transmitted to us from God’s inner sanctuary. If the breath of God could produce clouds that punished fields of men, then I was raised always braced for the exhale.

Our family home was a domestic church, its archways wreathed in Celtic Crosses and swirls of smoke from Marlboro Lights, our nicotine-stained rooms protected with small cement statues of saints meant for the garden. Symbols of the divine were often festooned upon the juvenile bodies of my brother and I by our grandmother to mark our mortality: medallion necklaces of St. Michael around our necks to cast evil from our souls; rosary beads around our wrists during vigils; ash on our foreheads in the spring for penance and to remind us that we are the dust from which God made us. We observed despite never being taught how to pray. And we believed, never knowing whether our prayers were received.

Faith is trusting that under the debris there is a lesson in the divine. That somewhere under the broken glass and busted fenders, in the concrete piling and insurance loopholes, there’s an element of the sublime that only God can show us. At least that’s what we were told.

***

It was a little Sunday in May. 2012. Newlywedded, my husband and I had just signed a lease on a split-level townhome. Like many women after graduating college who weren’t sure who they wanted to be or where they wanted to live, I married an older man and moved away from everything I knew, scarpering from one small town in Missouri to an even smaller town in the Rocky Mountain foothills. We met when I was nineteen, the age when it seems adulthood can’t come fast enough. I had spent adolescence praying for my own life— one far away from factory closures and watching my dad and his buddies drink away their severance checks at the Rearview bar in Saint Joe—and was sent someone with a decade more experience who came from a good, country-club going family. As my brother followed his artistic talents out to the east coast, I was told that marrying up was God’s will for me. Afterall, my parents didn’t know how much longer they could wait for grandbabies.

On that little Sunday morning, I was in the basement unpacking boxes with the years—1999-2004—scribbled on the side in black sharpie. Cardboard containers filled with the keepsakes of a young person: concert t-shirts, birthday cards from aunts, stray polaroids of me and high school girlfriends in crop tops and the original wide-legged JNCO jeans. Pictures of four girls in a car, each taking turns with the camera: two in the backseat blow kisses, one in the passenger seat throws a peace sign, from the driver’s seat I give the finger. Several of the photos were hazy from all the hot boxing. Other photos show clear shots of the two backseat bodies hanging halfway out the window in the fresh air, their bare stomachs and belly piercings lit by streetlamps. Those pictures were taken moments before I steered our low-riding sedan through manicured grass in the northside subdivision where the rich kids lived. Yardfarming is what we called it. Of course. Our tires left behind a jealous trail of mud and busted sprinkler heads. We secretly wanted to live on those quiet streets, far from the gun pops and squalling sirens on our block. We were supposed to want to marry those lawns, not destroy them. Those lawns, each wet and fertile in God’s perfect image.

Upstairs the local news broadcast played like a pop song through the radio. Obama had just been re-elected under the slogan “Forward,” and all the headlines seemed benign back then:

“Rothko’s Orange, Red, and Yellow Sells at Auction for a Little Less than ninety Million”

“Warm Days Bring Bear Cubs Out of Hibernation Early”

“Bear Found In a Slumber on Picnic Table Near the Student Union”

Bear gossip bustled through our little mountain town that week. Neighbors stood at their detached garages and discussed the sightings, a tickle of envy in their throats. Who wouldn’t want to see an American Black Bear up close?

That morning though, there was a new buzz in car stalls. Starting at 6:00 pm, the local University was hosting a solar eclipse viewing inside its football stadium with specialized paper-goggles and unlimited concessions to accommodate a full arena for the duration. Because an annular is not a blink-of-an-eye-event, like a total solar eclipse. But rather, an agonizingly slow two-hour spectacle, a stretching release of celestial spirits.

All the twenty-somethings in my office, the people my age, messaged in a group text that they were going early to secure seats on the upper deck. All week they had been planning. They were going to dress in animal onesies that zip in the front and take mushrooms to enhance the action. A lion, panda, unicorn, baby tiger. We need someone to wear the bunny suit, they typed, Katiy?

Costumes? Drugs? Going out after dark? AND on a work night? Didn’t they know that’s not what married people do? Instead of texting back, I listened to the chatter outside of my window. Women were making plans. Their voices flooded my body with want, a need to be part of their conversation.

The high was a dry seventy-five degrees. In the shade it was closer to low sixties.

Kids on the sidewalk practiced their reactions. They held their flimsy glasses tight on their little faces and shrieked at the sky. Chalk illustrations of red circles drawn at the entrance of White Plains Drive. Doodles of color amid the white mailboxes and slick white sneakers coming and going across the white concrete.

Near a cutting board I rolled my denim sleeves and started to slide wooden sticks through folded prosciutto. Nothing fancy. Finger food we could bring to the casual gathering at the carport next-door. I cubed melon to the tune of a piano and Garrison Keillor’s folksy voice in his Minnesota Public Radio show A Prairie Home Companion, my husband’s favorite. The week was a rerun of an episode featuring Martin Sheen acting as a cowboy named “Billy Bob” to Keillor’s character, “Lefty.” My knife quietly slid, and my husband audibly laughed at the word play, rhyming verses that ended in drum, plum, and dumb. Horse hooves and whinny sound effects. I didn’t find the show appealing. In fact, I loathed the show. Yet every Sunday, I stood in the kitchen and listened to my husband rhapsodizing over the joys of growing up with this old broadcaster in his ear. I didn’t get it. The things that awed each of us couldn’t have been more different, he was the morning, I was the night. I wanted loud, undistinguished bodies beating together in the dark, he was content with the quiet hum of a kitchen with a dishwasher.

When it was time, we walked outside. I displayed the platters of skewers to a small group standing idly, a few of the women who I had overheard earlier. My husband unfolded our mesh camping chairs, and just like that we fit in. As though he was reserving our spots for the next decade in that bright white driveway. A kid put a wooden skewer between his knees, threw his arm up with a YEE-HAW. Had he been listening to Garrison Keillor too?

Prevailing winds whistled from the peaks of the Flatirons; screeches funneled down the canyon. Pinecones jostled loose and fell to our feet.

It was chilly and then calm. Even the children were behaving. It all felt too sweet. White chocolate. How the kids stayed within the parameters set by their parents. Away from the sharp hedges and wet lawns that separated our corporate housing complex from the cul-de-sacs with larger homes. Tri-level designs with attached garages that belonged on billboards advertising dreams of the middle class. Not my dreams, but his. The cul-de-sac lawns had a better view of the sky that extended beyond our tree line. Though, no one in the cul-de-sac was waiting for the eclipse.

Then it was time, a man appeared from the shadows in a welder’s mask. He taught at the university and had established himself as the resident academic and now eclipse expert. Which meant from that moment onward he would announce the when, where, and how to look at the sun.

Shapes were happening, shadows hidden under clouds. Less than two hours were left.

We didn’t have telescopes or professional cameras. No pairs of the paper viewing goggles from the city. The professor kindly let people take turns wearing two metal hoods.

I rummaged around my husband’s Subaru Outback looking for a filter. Canvas bags filled with more canvas bags and a soiled cycling kit. It was all too typical. In the glovebox, was a sleeve of my old CDs, burned copies of albums from Nine Inch Nails, Bush, and Stone Temple Pilots. I handed out discs to the kids and few women left standing.

We could see the shadow of the moon inching across the sun’s corona. Slow and undramatic. Like someone holding a thumb up to thwart the sun. My husband carefully placed the welding helmet over his ballcap. Every few minutes he would lift the heavy metal plate halfway and sip his beer. Then wave his hands to move the clouds.

In the football stadium, everyone was instructed to stand, face the east, and blow away the clouds. Blow them back. Blow as hard as they could.

Unsuccessful, everyone in the town sat and waited through several false starts. Instead of watching a phenomenal tango between the moon and the sun, we were left with the dance of the cumulus coming and going. A tease.

After an hour necks became tired. Heads drooped to screens in laps. Carol, our landlord stopped by on her bike, but quickly became bored by the slowness of the clouds.

One of the children asked why was nothing happening?

I turned to my husband and asked, why was nothing happening? He had removed the metal mask and was answering emails.

The kid asked if this was it. I turned to my husband. Was this it? He didn’t know. And pointed out that I had a phone too. I could look it up.

Some of the older kids were playing tag. Chase me, they screamed. Chase me! So, I did. I lapped around the chairs of adults who pleaded from their seats for us to drop the skewer sticks. I squealed when cornered near the lawn’s edge and tagged ‘it’ by a tiny hand. It was getting late. Everyone had moved on from the eclipse. And then the clouds parted.

Adults motioned for us to look up.

Look up!

Look!

Look!

Wind carried cheers from the stadium. Did we witness the famous crimson sky? An airfield of red? The glowing horizon of blood red doom we imagined; the kind of sight you’d see in a video game that sends a bolt of cortisol through you? No. We didn’t see any of that. There was no pulsing ring of fire as we were promised. Only southern areas in Arizona and Texas could see the rare annular ring. Not even the professor knew we were only getting a partial.

Look! Look! The adults pointed again. If you look hard enough, you can almost see something, the professor said. The adults stood. Applauded. My husband beamed; he was satisfied. As though, this was what he had anticipated all along.

I didn’t look up or cheer. I didn’t want to settle. I wanted a ring of fire.

Well, what did you expect? my husband asked.

***

In her famous Total Eclipse essay, Pulitzer-Prize winning author, Annie Dillard writes her account of the total solar eclipse of February 26, 1979, as witnessed from 5-hours upcountry from the Washington coast, where she and her second husband, anthropology professor Gary Clevidence lived at that time. In this piece, Dillard exhibits her unique ability to find new, surprising ways to describe the indescribable:

“At once this disk of sky slid over the sun like a lid. The sky snapped over the sun like a lens cover. The hatch in the brain slammed…There was no sound. The eyes dried, the arteries drained, the lungs hushed…It was all over.”

Two years had passed since she had witnessed the phenomena before writing about it. And while she acknowledges that she had forgotten many things, what memories remained and made it to the page are nothing short of specific.

Though, what I love the most in Dillard’s Eclipse essay is her depiction of Gary, her second husband. Gary and the telescope. Stringy crinkles around his eyes moving, his voice muted by the wind. Together. Screaming as a wall of dark shadow came speeding at them at 1,800 miles per hour. Lines that reference Gary are sparse, but throughout each page his presence is felt, their partnership playful, two curious kids chasing a thrill. Married and living in awe.

Side by side, they lay in bed, him reading, her admiring the hotel artwork—a portrait of a clown with a cabbage skull—on the wall. Gary puts the car in gear and off they go, just as they had gone on “one hundred other adventures.” Not “many,” but precisely “one hundred,” an angel number, the utter spiritual alignment. In Numerology, 100 symbolizes completion. Embarking on the eclipse: adventure 101 for her and Gary. A new beginning.

Then the event is told in a series of statements beginning in ‘we’:

We pulled off the highway…

We climbed and rested…

We passed clumps of bundled people…

We tightened our scarves and looked around.

Once on the hillside, sky begins to change, the sun sets behind mountaintops, and Dillard writes: “‘Look at Mount Adams’ I said, that was the last sane moment I remember.” She moves back into the “I”:

I turned back to the sun.

I was watching a faded color print of a movie filmed in the Middle Ages;

I was standing in it…

She sees Gary in film. They are together in the physical form, but, separated by lifetimes of consciousness, wars, the fissures of humanity:

“The sight of him, familiar and wrong, was something I was remembering from centuries hence, from the other side of death: Yes, that is the way he used to look, when we were living…Gary was chuting away across space, moving and talking and catching my eye, chuting down the long corridor of separation.”

After the eclipse, she doesn’t return to writing of her and Gary as the adventurous twosome. At least not in that essay. Maybe not ever. In the final paragraphs, she instead posits at the chaos of the living. How only God knows when our time on Earth is up, and that could be while watching TV or while working or while waiting for the moon to pass over the sun. And what if after witnessing all that, “nothing changes, nothing is learned,” she writes. “Or you may not come back at all.” In my tedious search for a model marriage, or perhaps signs of another marriage’s last breath on the page, I had lost sight of the larger landscape.

Which is that for the Eclipse essay, Annie and Gary are a unit. Marriage as the ultimate motif for totality. For obliteration. Just as the sublime, love and its fragilities can be an opening—a portal into self-understanding.

***

My lineage is not one of eclipse chasers, nor of cosmologists or physicists, but is an ancestry rooted more in religion. All roads toward transcendence must first pass through the toll of the Lord. Our family wasn’t huddled together around the dining room table with bibles, but rather scattered across the brown living room carpet in front of the TV.

Growing up in the nineties in Saint Joseph, Missouri, I sought out the sublime through screens and books. Films like Little Shop of Horrors fed my lore of the supernatural: A flash of green light shoots across the downtown bow, an extraterrestrial plant with a mouth appears at a struggling flower shop. Was it an eclipse? Was it God? All I knew was that I was interested in finding out. Much like after I watched Kevin Costner play a farmer in Field of Dreams and suddenly all cornfields had the potential to attract the ghosts of baseball legends. We’d pedal our single speeds along the stalks on Riverside Road—past the seniors stomping on beer cans then hurling empties into the distance—and I’d pretend to hear the green furrows whisper incantations above our heads…If you build it, they will come…Or two-hours and forty-five minutes into Magnolia, when director Paul Thomas Anderson made it rain frogs in the San Fernando Valley. Cascading amphibians from the sky into swimming pools, exploding on windshields. My brother and I watched this cinematic reinterpretation of the Old Testament’s Exodus 8, and I, young and naive, turned and said how I wanted our own sacred frog storm. What I meant was that I wanted to be in awe.

However, accessing the sublime second-hand through a screen is like learning to ride a bike by reading. Skimming the Wikipedia pages of ancient Greek mathematicians to grasp the center of the unknown universe. Tying shoelaces and calling it a first kiss. We cannot force a big feeling. All we can do is pray.

***

When married your world can shrink to the size of held union. This happens over time, or sometimes overnight. Along the way of my shrinking, my line of sight had fallen below the trees. My gaze fixed entirely on the ground in front of me. It was impossible to gauge the size of my surroundings or consider what else was out there. When do you know a marriage has drawn its last breath? Is the question instead, when did we decide to stop running into the heat? Had I given up on being gob smacked by terrifying wonder?

The Sunday of our annular eclipse in Boulder, I watched my husband and neighbors adjust their excitement, and redirect enthusiasm meant for a sudden and complete darkness. No one tossed a beer bottle in protest of the partial. Not an audible sigh or hint of dissatisfaction. Everyone stayed seated in their individual folding chair wobbling atop the pristine concrete as they clapped. They just as well could have been cheering for an ice cream truck or the credits of a PG-rated transmission of the sun. No lips, no tongue, no adrenaline. Not one butterfly.

I reached for my husband’s hand. He batted my palm away like it were a hot coal.

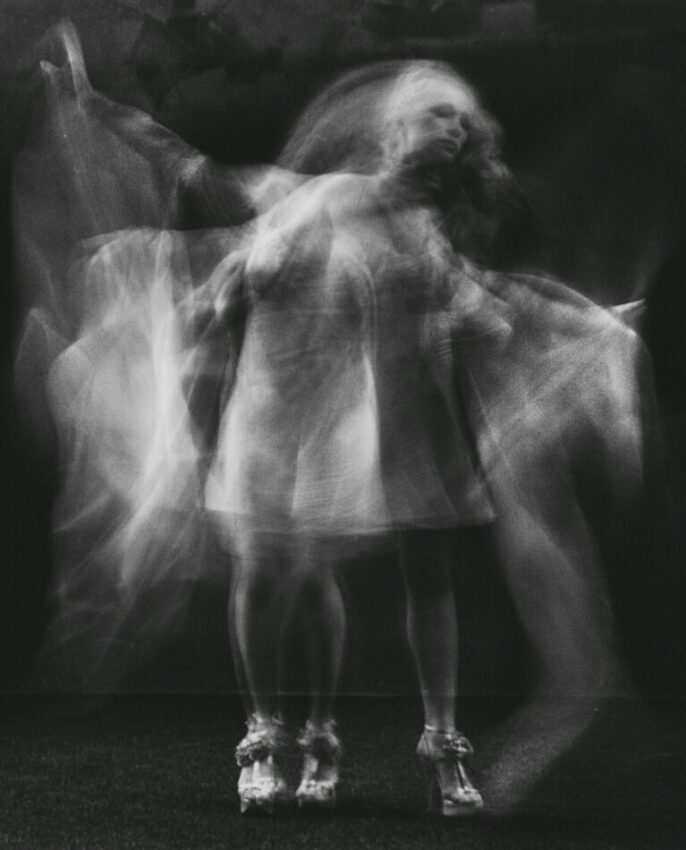

The lion, panda, and unicorn friends from the office somehow in their state texted updates from the stadium. Reports of floating forms. Geometry, but erotic. One is certain she saw the moon and sun have sex. They were changed.

Children, my husband called them. Asinine. He was so glad we were past that phase in our lives. He must have meant the phase where we have fun. To an outsider, we remained the same.

Dusk. Now that nobody was watching, the clouds finally cleared to show stars as white specks amidst the purple streaked heavens. Most see this time before the evening as a type of days end, but if you can separate fear from beauty, infinite possibilities can emerge from the dark.

I wasn’t supposed to make it as far as I had all things considered. Poor family. Public education. I should have been grateful, he often reminded me. All I wanted was to fill more boxes with new polaroid pictures.

***

Annie Dillard and Gary Clevidence remained married for nine years after the total solar eclipse.

***

My husband and I would remain married for six years after the partial eclipse. Though, that night I was already starting to change. A flake of my soul spiked from the center of my desires, tugged upward by the moon, then broken off entirely, recommitting itself to the wild.

One of the young girls asked if I wanted to play one more game of tag. Panting as she asked. Hands covered in either dirt or chocolate.

Sorry. Time for the grown-ups to go inside, I said. Then lifted my right hiking boot up high for show of strength and brought my foot down hard crushing a half-empty can, craft pilsner spraying out in her direction.

KATIY HEATH is from Saint Joseph, Missouri. Her writing has appeared in Joyland, Catapult, HAD, XRAY, among others, and has been supported by Millay Arts, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (VCCA), and NES Artist Residency in Skagaströnd, Iceland. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College. For more, visit her website at keheath.com.