Global Voices Interviews *Hungary* Kinga Tóth & Timea Balogh in conversation with LIT's JP Apruzzese

The Hungarian version of this interview is forthcoming in Aprokrif in early 2021.

In Kinga Tóth’s world everything is alive and moving and coalescing at each moment. Separation and disconnection are notions she considers unnatural in the natural world. In her work, the multimedia artist and poet captures what most of us neglect to see – not so much the interconnectedness of everything – which suggests the possibility of disconnection – but rather the relentless and organic becoming of everything into one living body that contains all animate and inanimate life. Where, as she puts it, “boundaries disappear…and [we] merge.” So that language becomes a living thing, an organism, whose integral parts include not only sound – be they letters or other speech utterances – but materials, such as the paper on which language falls, the ink through which it appears, and stretching further, the tree that gives its life. This materiality of language, Tóth says, can be felt. Sound is tactile – a word can send shivers down your spine. “Language is an organism that gives you experiences,” Tóth reminds us and lifts the veil on a fascinating universe – which is our own after all – so that we can fully recognize and partake in its rich unfolding.

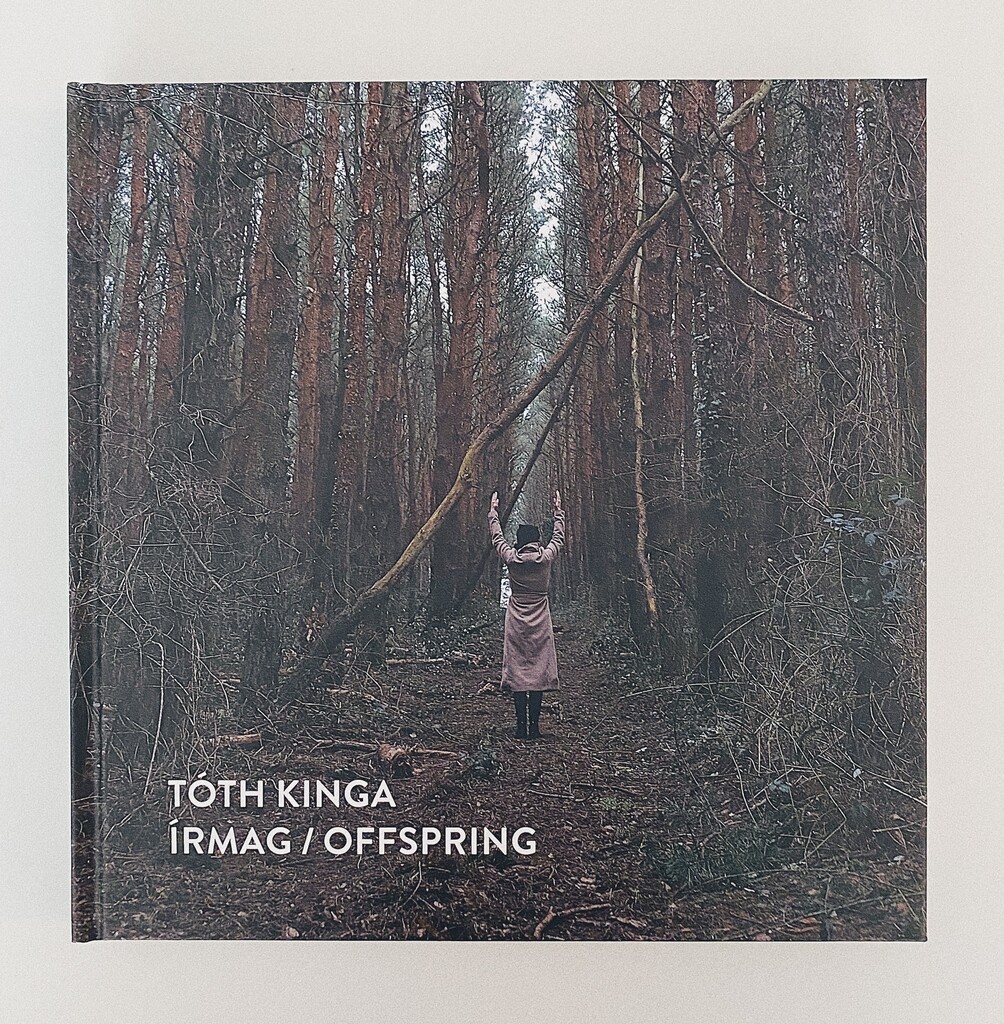

In April 2020, we were thrilled to bring Kinga Tóth’s voice to the pages of LIT in excerpts from her recently published poetry collection, Írmag/Offspring. Her collection is a manifestation of this rich unfolding, which comes to us thanks to the superb translation by Timea Balogh, Hungarian-American and short story writer living in Budapest. Balogh felt an immediate affinity with Tóth’s unique vision and expression and, in her own storytelling, explores the quite natural merging of the real with the fantastical. Her story “The Stone Men,” recently nominated for a 2021 Pushcart Prize, plausibly imagines a woman bumping into a man she first thinks is real only to find out he’s a statue. From here – a moment in a garden – unfolds her fantasies recounted in a compelling, humorous voice, turning the tables on conventional gender perspectives to great effect. Like in Tóth’s work, this stone man becomes animate, naturally. In this time of pandemic, Tóth says, “Culture has perhaps never played such an important role in making up for this personal contact.”

***

I believe in life instead of narration

Kinga Tóth

You are from Hungary and now live in Germany. Tell us about this journey and how it has defined your concept of home.

Kinga Tóth (KT): I’d put it this way: I’ve been living as a nomad for the past eight years. I moved from one place to the other with the aid of different grants, as I didn’t have sufficient funds to keep renting a place. In 2015, I stopped renting my last place, and since then I’ve been living all over the place. I am at home being in transit and love being in transit, not only physically-geographically but also in terms of artistic movements and languages. But there is indeed a single place where I kind of feel at home, which is our vineyard. It has a cellar and is located in Nyőgér, a small city in Western Hungary. I would love to own a wooden holiday cottage and spend my summers there.

And, Timea, you were born in Budapest, grew up in California and then returned to Budapest as an adult. Tell us about this journey and how it has defined your concept of home.

Timea Balogh (TB): I only lived in Los Angeles for the first four years after my family and I emigrated. I actually grew up in Las Vegas. I haven’t yet found the vocabulary to write in my fiction about the desert that God turned its back on. I’m sure that’ll change soon though. I’m already writing about it in the poetry I’ve been writing in Hungarian. I suppose it’s my unconscious desire for the two cultures to understand each other, so when I write in English it’s primarily about Hungary and when I write in Hungarian it’s primarily about America. Home is a very fraught concept for me. As is belonging. I feel at home in Sin City and in Budapest—not in the same ways, though—but I also don’t feel like I fully belong to either. I will never understand Thanksgiving or football, nor will I understand the wake of communism or how to write in my first language as though I were a native. I often have to remind myself that I have two homes so that I don’t get stuck feeling like I have none. Hungarian actually has two words for home. Itthon means here-home and otthon means there-home. The words exist because the grammar of the language requires that the speaker specify whether they are at home or not at the time of the utterance, but it comes in handy in times like this. Budapest is my itthon, Vegas is my otthon.

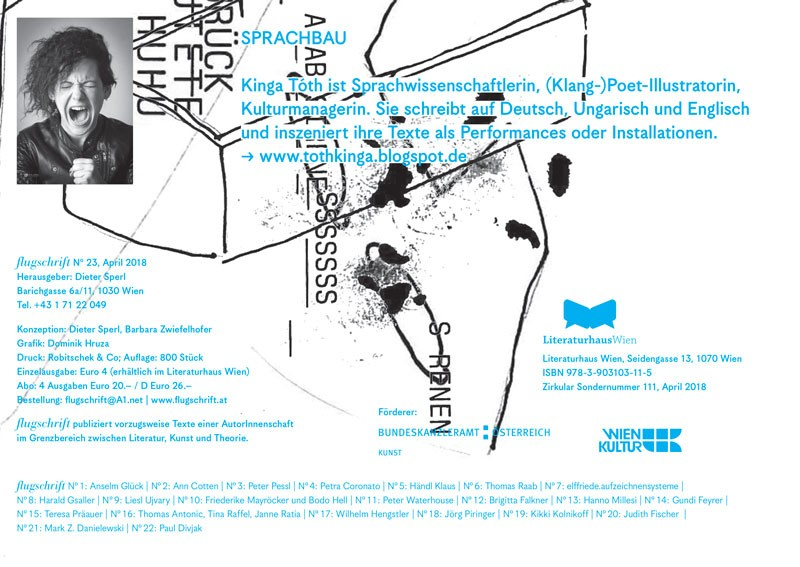

Kinga, you have gained the admiration of your peers and won awards in different artistic fields. You are a multi-disciplinarian. Can you tell us about your trajectory as an artist, writer, poet and musician? How do you see the connection between these different modes of expression?

KT: Actually, there is no need to seek connections between the different fields, as in my world there is no difference between them, it’s one body, a living text body. Honestly, I don’t like these ‘stamps,’ these brands. I create living linguistic and communicative spaces with sound, picture, letterform, different languages, spaces, and performance. It’s when I also gain a space, one that I can populate with my creations to my heart’s content, that I feel this world truly works. To me, this is what performative literature is that is alive. My first steps were hard, the literary field had a hard time accepting my works, which is part of the reason why it’s a great joy for me to have received the Hugo Ball Förderpreis award this year for my German-language, interdisciplinary, performative literary output, and more recently the Bernard Heidseck award from the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the Italian Bonotto.

You’re recognized as an emerging writer and translator, Timea. Can you tell us why you’ve chosen to become a translator? And how do you view the craft/the art of translation within the wider realm of literature today?

TB: I’ve essentially been translating all my life, a statement I think true for most children of immigrants. My first language was Hungarian, and I greatly admire those Hungarian translators who learned the language as adults, especially those with no direct ties to the culture. The language differs drastically from Indo-European languages, and there are less than fifteen million speakers worldwide. I’m grateful my parents were adamant I continue speaking Hungarian with them once we immigrated to the States, otherwise I would’ve forgotten it completely. I earned my MFA at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where all creative writing students are obligated to spend time abroad and complete a translation project. I used the support of the University and The Black Mountain Institute to visit Budapest regularly for long periods during grad school and attended readings, festivals, residencies, literary events of any and all kinds here, which kick-started my translation career by exposing me to the writers I later went on to work with. In this way, I didn’t choose translation so much as I was led from early on in life to become a translator of my native tongue. The effort always was and will be to establish a stronger and more intimate connection with my roots. In terms of translation within the wider realm of literature, I have to say it’s incredibly unfortunate that we have to make a case for translation in the U.S. We’re talking about the literature of every other country and culture besides ours, and yet translators are consistently burdened with having to “sell” the value of it. This is a uniquely American problem that the rest of the world, or Europe at least, doesn’t share.

The poet, no longer in a privileged position, exists, survives, and transforms, together with nature, with the materials. – KT

So delving in deeper, Kinga, at LIT we were thrilled to publish excerpts from your collection of poetry entitled Írmag/Offspring. The voice in Írmag/Offspring seems to be that of the elements themselves, the earth, the vegetables, the animals. And yet the voice itself feels fragmented, as if you the poet are listening to them speak in a foreign language, one you are still learning. Can you tell us how you came to compose Írmag/Offspring?

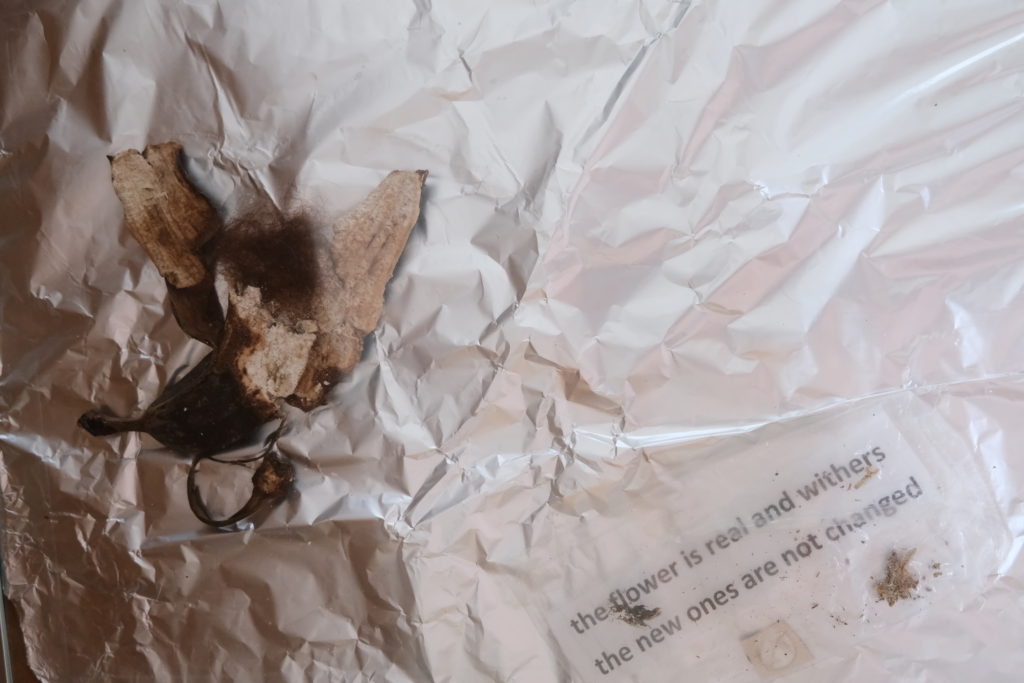

KT: First of all, I am grateful for Timi’s hard work and the opportunity to have my writings appear here. What you’re asking about is complicated business; the poems originally entitled Corn Songs have since come under the title Írmag/Offspring, part of an art book in which drawings, graphics, visual-video-audio works can be seen. There was an exhibition where animate and inanimate matters, rubbish, and remains all came into dialogue with each other. My goal is to make boundaries disappear between the categories of animate and inanimate, plant-like and animal-like, organic and inorganic, feminine and masculine; and, like in the poem “Octopus,” to have us merge into new “love-hybrid-communities” after the apocalypse. The poet is one among those who remains and whose recollections we are listening to after the eco-disaster. The poet, no longer in a privileged position, exists, survives, and transforms, together with nature, with the materials.

Your work questions our assumptions and expectations about language, its origins, structures, and uses, and in that sense seems to echo the work of thinkers such as Barthes, Derrida, and Kristeva. We get the sense that language fails us, entraps us, forces us through a labyrinth of convention out of which there is no escape. And yet you continue to create. What is your approach to the creative process? And how do you reconcile the apparent contradictions?

KT: I think language is a living thing, which could be taken as an organism, but should not be thought of as a linearly evolving mass that has a beginning, a peak, and then an endpoint when it passes away. Regardless, language is organic because it moves in the world, between language areas, it evolves, mutates. Language usage depends on sound, biological organisms, people, history, and the current era, in the first place; if it is spoken, it has a sound. For instance, you cough, snort, clear your throat while using language, and because of this something happens with the medium of language, which has an effect on language itself, and this you can write down using letters, you can “letterize” it. This all happens, as it were, “into” the medium. I don’t think these can be separated, I believe language is constantly happening, is constantly being used, is constantly changing. And, certainly, the sounds we call extra sounds or subplots are just as integral a part of it. To be more specific, take gurgling or choking as examples – or take how I am now going to sneeze or cough in the middle of all kinds of sentences. The same thing happens in a book. Okay, there, you have a set of sterile letters, but let us not forget that they are printed on paper, which means they have a medium, and the medium in turn has a history, and all of this has a materiality. Even computers have mediums, as you read on a screen, for instance. So then why aren’t they environmental factors? Why wouldn’t they be a part of language? Language, after all, comes alive in them.

Linguistic elements (visual, audio, text, performance, etc.) do not mix but live because they are not separate. They can be separated if that’s the purpose of my game. If I say visuality, then that’s going to be the medium of language; if I say sound, then that; and if I say these two together, then them. But if my intention is to reach you with language, to connect, then sooner or later you will also have a say in the matter. From then on, it’s the two of us playing, and you can say that for you it’s sound, and I can say that for me it’s images. Or that for me it’s like I felt a snail’s slime when saying, “bless you.” I can feel that it’s on my skin, which, again, has a visual but also a tactile effect. You see, language is actually an organism that gives you experiences. In literary theory, too, there are about 25 models for analyzing texts. All of them are relevant at the same time. If one can accept that multiple critical approaches can be valid – one thing and even its opposite – then one is freed from the need to reduce things at all costs, because categorization immediately becomes invalid. I would say instead that the most important thing is the game and the freedom of the game. And the question is whether I let my game move freely or I would like to categorize it by all means. And if it’s the latter, why do I do that? Because it offers security? Although we have language frameworks, linguistic codes, and different systems, we have only created them to reassure ourselves.

I believe in life instead of narration. Literature lives, the author is but one component in the process, in the merging. There is no need for death or for withdrawing from processes, we connect, gain experiences, and spread as organisms. –KT

How do you view Roland Barthes’s theory that sees the death of the author as a necessary component of the narrative experience, that the writing and the creator are unrelated?

KT: As I wrote above, I believe in life instead of narration. Literature lives, the author is but one component in the process, in the merging. There is no need for death or for withdrawing from processes, we connect, gain experiences, and spread as organisms.

Turning to Timea, though bilingual, you have chosen to write in English. Tell us how you came to this decision and how you balance the cultural chasm between the two.

TB: It wasn’t at all a decision but a product of my upbringing. I was raised and educated in the U.S., which means that even though we spoke Hungarian at home, I’ve spent the vast majority of my life thinking, speaking, reading, and dreaming in English. The ratio of English thoughts versus Hungarian thoughts in my head have only recently begun to shift, as I started spending more and more time in Hungary, but my complex and eloquent thoughts in English still greatly outweigh those in my mother tongue.

I constantly struggle with improving my Hungarian while also maintaining my English. My first year of living here taught me that your dominant language can, in fact, deteriorate by a shocking degree. I was living and breathing so much Hungarian that not only was I thinking in it all the time, but I also took the leap of writing and even performing slam poetry in Hungarian. Meanwhile, though, I couldn’t seem to string together an intelligent sentence on the phone with friends back in Vegas. Luckily, this condition is quickly reversable. One summer spent in Amsterdam among English-speaking company was enough to do the trick. Now back in Pest, I’m curious to see how I fare with the balancing act this round.

There is an affinity between your work and that of Kinga, a sense of transgression and razing of barriers. What attracted you to Kinga’s work that you felt impelled to translate her poetry into English? Share with us the story behind your collaboration.

TB: I was volunteering at the József Attila Circle’s literary tent at the VOLT Festival in Sopron in the summer of 2017. Kinga came to perform there and blew me away with her strange and intoxicating vocal performance. Later, Kinga reached out to me over Facebook and said she was looking for an English translator. While I was reticent to translate poetry at the time, I read her work and found it so unlike anything I’d read in any language. It was just strange and weird and experimental enough for me to try my hand at bringing it into English. We maintained correspondence online for over a year before meeting in person for the first time, a common experience for most translators and their writers, but a new for me and my process at the time.

Do you have a similar connection to music, sound, and performance that we find in Kinga’s work?

TB: I’m not musically inclined unfortunately, but I do love being behind a microphone. I learned in my MFA through readings I gave just how much I love reading my work in front of an audience. After moving to Budapest, I sort of stumbled into my first slam competition, which I performed in English and actually won, and that forced me to recognize how much I cannot get enough of performing. After that, I sought out every opportunity I could to get up on a stage, and when I felt that it still wasn’t enough, fellow translator Owen Good and I started a monthly reading series in Budapest called Mudjaroo! Hungarian Literature in English, where I’d read both translations and original work.

A language of lies, a rhetoric of lies is at work, which from time to time does drive me to scream out in anger. –KT

Kinga, your hybrid collections I don’t wanna, Party, Sunflowerwomen, and We Build a City, combine poetry and illustration and seem stylistically to reflect the work of contemporary authors such as Renee Gladman. These collections have a palpable rage at and preoccupation with volatile family life, the condition of women, and the treatment of animals and nature. Can you tell us a little more about the origin of these collections?

KT: These earlier works of mine (like all of my works) indeed reflect the society surrounding us; a poem of mine entitled “Kelemenné” has just been published in Hungary and Germany, it was translated into English by Annie Rutherford and is another one that addresses the topic of domestic violence. In Hungary, a woman dies due to domestic violence every week, and 15.000 abused children are registered every year. The local government, however, claims that the Hungarian family is sacred and there is no aggression in it. A language of lies, a rhetoric of lies is at work, which from time to time does drive me to scream out in anger. I was blocked on Facebook for a while due to my poem until they examined my profile and eventually concluded that I was not making untrue statements, so I could get back a part of my virtual self. How dangerous a poem can be! 🙂

I strive to speak in the name of acceptance and equality, and my poetic voice also tends toward that direction. My first volume to be published was Party, maybe that is where this voice can be heard the most directly; there, anger and despair still dominated. Today I speak more peacefully, asking to respect, pay attention to, receive, accept the other. Perhaps this is the position of the nun who speaks in the feminist prayer book I’m working on.

Timea, Your short stories The Stone Men and What They Call It uncannily marry reality with fantasy in a gripping exploration of women’s sexuality today. Stylistically, they echo the conversational cadence and intimacy of Miranda July and the otherworldly imagination of Michal Ajvaz. Tell us about your approach to writing.

TB: First of all, what an honor to be compared to these writers. I once had the immense privilege of hearing Miranda July read during one of the Believer Festivals in Vegas. In advance of the event, she asked the women of the audience to anonymously submit their deepest sexual fantasies, which she went on to read aloud to us without any commentary. It was such a powerful act. Some of our fantasies were risqué and transgressive, but the most stirring were haunting and poignant. Then July read a story that was solicited but ultimately rejected by Playboy in which a woman has sex with her dog, and the man smoking a cigarette on the balcony of the downtown weekly next door to our outdoor reading blushed and ran back to his room.

I most often write magical realism these days, which is something I learned to do from the emerging Transylvanian magical realist Ilka Papp-Zakor, whom I’ve been translating for the past five years. It was through climbing inside her stories and turning them inside-out, turning them into a different language, that I grasped the structure of magical realism. Of course, that learning process started by reading masters of the form like Aimee Bender, but I read her for years without being able to replicate what I found between those pages. Papp-Zakor’s stories led me by the hand into these new landscapes.

In terms of content, I typically start with a concept. For “What They Call It”, I knew I wanted to list and compare Hungarian and American euphemisms for vagina, so I built a story around that. After having the initial idea, it can take me years to finally learn just how to tell it. “What They Call It” sat on my desktop for a year as a file titled “Vagina Story”.

It was a similar case with “The Stone Men”. I’d heard a woman on The Moth podcast tell a story about a lover who was some twenty years her junior. The woman had a slight accent that made me mishear “he was a sculptor” for “he was a sculpture”. That got me toying with the idea of what it would be like if a woman were dating a statue. I’d just recently returned from Verona, where I’d visited the panoramic Giusti Garden, laden with statues at every shrub, so I imagined a woman bumping into a man there she’d at first think to be real but would quickly come to realize is an animated statue. I was really excited by the idea, but I didn’t know where to take it, and it was only a year and a half later, when I was finally able to write the story, that I realized it wasn’t working before because I wasn’t familiar enough with Verona. Once I moved David of Michelangelo’s copy to Budapest, I could write the story to the end without pause, because I know how this city pulses and breathes. And Budapest itself is full of sculptures, not just the many monuments, but every façade, too, and Kerepesi Cemetery, often called Fiumei after the street it’s on, has particularly captivating ones. These are just some of the ways the city is a deep well I draw from for my writing.

[Miranda July] asked the women of the audience to anonymously submit their deepest sexual fantasies, which she went on to read aloud to us without any commentary. It was such a powerful act. Some of our fantasies were risqué and transgressive, but the most stirring were haunting and poignant. –TB

Your poetry feels deeply experience-based and personal. Considering Kinga’s affinity for Roland Barthes’s work how do you view his theory that sees the death of the author as a necessary component of the narrative experience, that the writing and the creator are unrelated?

TB: If memory of my literary theory and criticism courses in college serves me right, Barthes’s theory applies to the reader, not the writer, so how dare you assume my poetry is personal! I am dead, and you ought not to make assumptions about the dead! Actually, I came to maturity, quite literally, in the creative writing workshop, having started taking them when I was seventeen, and the Iowa Model, which academic workshops overwhelmingly tend to follow, is very much in line with Barthes’s philosophy. In workshop, we critique that which is on the page, not wasting time on what the writer may have meant. What did she say verbatim? If she meant something else then she should say that it in her next draft. My poetry is indeed deeply experience based and personal. As is my fiction. I still struggle with distancing my characters from me. It’s hard when you’re your own starting point for your characters. Hopefully someday I won’t find myself so goddamn interesting as to write about “myself” all the time. But even then, I still see the world through my characters’ eyes as I’m writing them, so that may not be such a foolproof plan after all, who knows. Even the characters who don’t resemble me still have me in them, in one form or another. I imagine it’s necessary to find that connection with a character, even one who’s totally unlike you, so you can tap into the emotional truth of the story, or the poem.

Thinking about language, Kinga, you speak and write in three languages, Hungarian, German, and English. How would you describe your relationship with each language? How do you view our collective relationship to language as a society?

KT: My mother tongue is Hungarian, but German entered my life at a fairly young age, we could say that is the sound of my chosen identity, the one that relaxes me, the one that lets me play, the one I know will never be perfect but for this very reason can give me the freedom for games, for creation. English arrived third and is a bit of a bastard child, our relationship is ambivalent, a creamy sensation in my mouth, I have a hard time forming it; my tongue, my throat is used to raspier sounds, they resound in a rawer way, maybe that’s why German and Hungarian are easier and, well, I also don’t speak English as well as I do the other two languages – albeit I talk with my friends mainly in English. Nevertheless, I need a translator who is familiar with my world and can help me make sure the text is present in the same complexity I conceive it. I have been writing in a hybrid-mixed language for a long time, my texts are produced in German-Hungarian, and then I refine them: I create a Hungarian and a German text. At performances, however, I love to use the mixed version. English comes after this, and it’s more like a language of the real translational process.

I am interested in crossings, in the in-between zone, in the same way as I am when it comes to genres. The text knows what form it will appear in, it only has to be allowed to appear. –KT

In articles and interviews, you are often described as a ‘sound poet.’ To the unadventurous ear, your musical or sound work can feel unconventional, even jarring, though in truth they very much reflect our daily urban environment. How did you arrive at this technique of composing? How do you understand the rapport between word and sound when composing musical pieces?

KT: As I said, language and texts are organic, they have their sound, their visuality, their flesh-body, their contours. Thus, there is no question about what music is, what sound is, what language is, what text is. These categories do not exist; there is only merging, life. I am interested in crossings, in the in-between zone, in the same way as I am when it comes to genres. The text knows what form it will appear in, it only has to be allowed to appear. The eventual act of composing is a far more conscious step, but even that often comprises of unbridled juggling and putting faith in the work and its role, its form. Like in mathematics, composing involves a great deal of virtuosity and improvisational space – like learning a foreign language, for that matter – one only has to let them happen.

Timea, as a Hungarian-American having returned to undertaken reverse-migration back to Hungary, what are your views of European literature as compared to American literature today?

TB: I can’t make any claims about European literature as a whole, because I simply haven’t read enough. I can, however, make some sweeping generalizations about contemporary Hungarian literature versus contemporary American literature. American writers are masters of plot. Of course, American writers have the privilege of a whole industry of plot specialists behind them, from MFA programs to agents to editors. In Hungary, where there are no MFA programs or literary agents, and where the market is much smaller and thus publishers are not competing to hold the audience’s attention, it should come as no surprise that Hungarian novels generally don’t have a tight, well-refined plot structure. There are, of course, exceptions. The late great Antal Szerb is one. Or in film, there’s The Land of Storms or Bad Poems. This is why great feats of Hungarian literature like Péter Nádas’s Parallel Stories have received such bad reviews from English-speaking critics. Nádas’s postmodern mosaic, which tells various and eclectic bits and pieces of Hungary’s fraught and chaotic 20th century is a masterpiece that’s bound to disappoint if the reader goes into it expecting a coherent story with a plot. And while we’re on the subject of long, historical novels, this is what Hungarian literature is most known for globally, and rightly so! There are fantastic examples of such works, but there are other hidden gems too, like magical realists Ádám Bodor or Ilka Papp-Zakor. Overall, though, I will say that yes, Hungarians are darker and more tragic than Americans. American happy endings, especially in movies, feel too expected to me nowadays. No one can cause you deep and aching pain quite like a Hungarian writer…perhaps a Russian. As for poets, the classics like Attila József and Sándor Petőfi are known abroad, but they don’t even begin to scratch the surface of the deep and multifaceted wealth of poets. To only speak of those writing today, you can find everything from the more narrative, prosaic poets, like Márton Simon, Tibor Babiczky, and Zita Izsó (the most prosaic of these three), to experimental and bizarre like Kinga or Kornélia Deres, to confessional like Lili Hanna Seres. This is of course true for American poetry, too, but the array of poetic diversity in Hungary is shocking for how small the country is. Perhaps the starkest contrast to me lies in spoken word. While Americans most often voice painful issues around identity and experience on stage, Hungarians tend more towards humor, audience participation, and calls to action. This surprises me most of all, since in every other genre Hungarians take the lead in pessimism.

American happy endings, especially in movies, feel too expected to me nowadays. No one can cause you deep and aching pain quite like a Hungarian writer…perhaps a Russian. –TB

As for literature as a whole, the two cultures treat their writers vastly differently. It’s true that Americans turn to writers on issues of politics and revere them in that way, as intellectual figures, and the same is true for Hungary. Here though, classical writers are national heroes. Every other street and square is named after a Hungarian writer. And not just in Budapest. The same is true for the countryside.

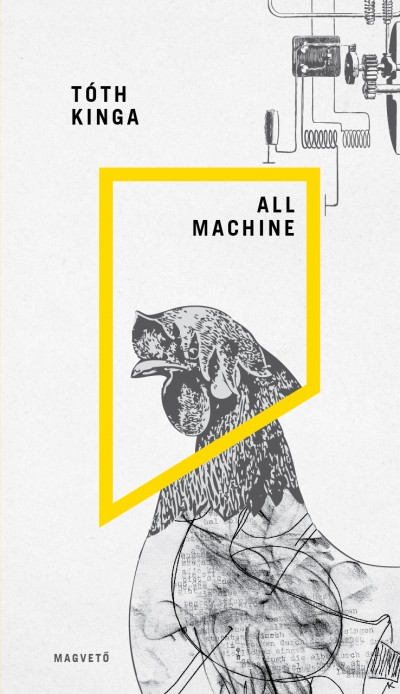

Kinga, how do you feel about the translation of your work? Are there words and concepts you feel cannot be transmitted from one language/culture to another without losing something essential?

KT: Translation is a very difficult area, one needs to create new works, and I admire the labor and humility of translators as they try to express the real essence of works to the best of their abilities. My case is especially difficult, since I create in a hybrid language, something between Hungarian and German, and I feel a work is complete when accompanied by intermedial pieces. That’s why in the beginning I tried to make English adaptations myself (like in Party, and with a poem or two in All Machine, Moonfaces, or even Corn Songs). However, for the moment, I’ve let this go; I simply don’t have the kind of relationship with English that I have always had with German. That’s how I came to ask Owen Good and Tímea to do the translations – they do adaptations from Hungarian – and I found Annie Rutherford for my volume in progress – she translates my latest prayer pieces from German into English. It’s hard to tell whether anything is lost. More like reshaped. At any rate, it’s a wonderful thing: letting go of constantly being in control and inviting others into the creative process.

And how have you engaged with Timea in the translation process?

KT: For several years now, a literary translation camp has been held annually in Dunabogdány, attracting translators from all over the world to translate Hungarian works into foreign languages – that is, their own mother tongues. With Timi, her bilingualism, her being Hungarian-American is awfully exciting, and so is her passage between languages, and since we would talk a lot anyway, there was no question I wanted her – first to proofread my texts, then, when I let go of my control over them, to translate them.

As a writer and a translator, Timea, do you feel, as some have claimed, that translation is the ‘art of loss’ and that some words and concepts are untransmissible from one language/culture to another? How do you approach what seems to be lost in translation and untransmissible?

TB: Of course, every language has untranslatable, untransmissible words and concepts. And the farther apart the two cultures are in terms of distance, history, religion, and what have you, the more untransmissible these words and concepts will be. Sometimes I’ll localize or homogenize the idea, meaning I take it out of the original context and find if not an American equivalent then a close-second. Other times I’ll leave the Hungarian word as is, either letting it stand on its own to pique the curiosity of the reader, inspiring her to look it up if she so inclines, or I’ll explain the word or concept, as I did earlier in this interview with itthon/otthon. But yes, overall, translation is without a doubt an art of loss. This is the natural consequence of losing the language it was written in, the primary reader for whom it was originally written for. But untranslateability and untransmissability are not a one-way road. English has just as much as Hungarian, so I try where it serves the text to take full advantage of the English language. Ultimately, any translator can practice the art of loss, but a translator must be bold to ensure the new text makes gains.

Women are socialized to not only be less self-serving, but to also listen better, consider other’s thoughts more, and to generally be more empathetic, all of which are skills necessary to translation. –TB

As a woman translator, do you feel women bring something different to the craft/art of translation?

TB: I find this question particularly interesting, because most translators are women, and most of the writers they translate are men. It’s an unfortunate symptom of the patriarchy that, worldwide, men feel more motivated to publish and are more rewarded for doing so, on almost every level. Meanwhile, women are more motivated (both personally and institutionally) to serve the words of these men yet they’re still not as rewarded for their work as their male translator colleagues. The Women in Translation movement recognizes the gender disparity first and foremost in terms of who is being translated, but it should also recognize who is doing the translating.

Women are socialized to not only be less self-serving, but to also listen better, consider other’s thoughts more, and to generally be more empathetic, all of which are skills necessary to translation. Everything should be done in service of the text, and I think women are generally more adept at putting their egos aside to accomplish this aim.

Kinga, where do you see your place within the world of European letters and art today? And how do you see your work addressing the issues of concern in Hungary, Germany, Europe and the world?

KT: I am always in transit between formats and genres, like I am between countries. Constantly in transit is how I like to see myself the most, this is what relaxes me, this is how I function. And of course, the locations of my travels occupy my mind, I make them mine, build them into my works, filter them through myself. I endeavor to offer an authentic, colorful image of these destinations and stops, trusting that I also invite the other, the audience to play, as much as possible.

I always tried to find my own voice, get quiet, focus inwards and let myself experiment, take risks, be myself, and be a good channel, medium. –KT

Can you share with us who your influences are, both early in life, in your career and now, in Hungarian, German, English, and world literature? And how have they influenced your writing and art?

KT: I never really had and still don’t really have role models. I always tried to find my own voice, get quiet, focus inwards and let myself experiment, take risks, be myself, and be a good channel, medium. But I do have to mention that my absolute heroine is Katalin Ladik. She’s not a role model but the role model, if there is such a thing. Unfortunately, I discovered her works late because I was so much in my own bubble, and she was in a bubble, too. It’s unfair how ignored she was at home for the longest time, even though her works were constantly exhibited abroad. The experts at home only began to pay attention to her in 2016 when she received the Lennon Ono Grant for Peace award, which was founded by Yoko Ono, and which she accepted in the company of such international artist-stars as Ai Wei Wei, Anish Kapoor, and Olafur Eliasson. A year later she was able to have an exhibition at documenta in Kassel. She’s ended up in the limelight again, and finally not only creates but also gets opportunities in the meantime. I think our careers are also similar in that we both walk our ways without compromises, standing up for our own voices.

Who are your influences within Hungary, America and world literature among writers, poets, and translators?

TB: There are so many fantastic Hungarian translators I’m proud to say I share the field with: Ottile Mulzet, George Szirtes, John Batki, Paul Olchvary, Judith Sollosy, Ildiko Noemi Nagy, Imre Goldstein (who translated Péter Nádas’ magnum opus Parallel Stories in just five years), Thomas Cooper, Anna Bentley, Owen Good, and many more. In terms of translators from other languages, recently, I’ve most enjoyed Jennifer Croft’s translation of Flights, which earned author Olga Tokarczuk a Man Booker Prize, Deborah Smith’s The Vegetarian, and, having spent the past summer in Amsterdam, I got a small taste of the incredible breadth of Sam Garrett’s Dutch translations through Jan Walker’s Turkish Delight.

With English prose, I can’t get enough of Carmen Maria Machado, Lesley Nneka Arimah, Sofia Samatar, Kelly Link, Catherine Lacey, Roxanne Gay, Aimee Bender, Manuel Gonzales, George Saunders (with whom I’m proud to say I share a mentor) Raymond Carver, Lorrie Moore, A.S. Byatt, the list is endless! For Hungarian prose I turn to Ilka Papp-Zakor, Éva Hutwagner, Nádasdy Ádam—who’s also a poet, but whose latest short story collection, A szakállas Neptun (The Bearded Neptune), about gay male relationships during the last thirty years of the communist regime is a phenomenal and deeply important work—the aforementioned Péter Nádas, Réka Mán-Várhegyi, and the classic Antal Szerb and Gyula Krúdy. More internationally, Italo Calvino will always be a favorite and Anaïs Nin—how are we to classify her? And with poetry, I can never get enough Olivia Gatwood, Kaveh Akbar, Hanif Abduraquib, Danez Smith, and Franny Choi. And the most stand-out Hungarian poets, some of whom I’ve already mentioned, most of whom I’m proud to say I’ve translated: Márton Simon, Kornélia Deres, Tibor Babiczky, Zita Izsó, Krisztina Tóth, Lilli Hanna Seres, Ágnes Kali, and of course Kinga. 🙂

How do you see the role of translation within literature today in Hungary, Europe and the world, and within larger issues of global concern?

TB: As I’ve already touched on a bit, cultures around the world use literature in translation to look past their own borders, stay up to date, and connect. Aside from travel, reading translated literature is the single best way to understand another culture. It’s even more intimate, in fact, because it allows you to look inside the mind, worldview, and inner world of someone who likely doesn’t share the same words as you do, may have entirely different understandings around essential human experiences like love or loss, or they may have the same despite the vast distance between you two.

Kinga, what are you currently working on and how do you see your work evolving in the future?

KT: I’m working on my newest intermedia-sound-text work called “Metamorphose.” This intermedial project is based on my biofeminist prayer series “MariaMachina.” In it, I treat ‘nun art’ and recycling as research materials. I consider nun art (fine art, writing, chanting, walking, gardening) a performative act, both on a physical and psychological-mental level and I treat recycling as a technique in the fine arts (usage-re-usage). I began my research in Graz a while back, and in 2020 I would love to finish it in Switzerland with the help of the Visegrad Fund. These texts are written in a language that falls between prayer and poem, creating the groundwork for further visual-sound performance. In 2020, we – my photographer-collaborator Kaspar Mattmann and I – spent two months in the aqb (art quarter Budapest) Project Space where we continued the photographic part of this project now under the name “Metamorphose.” Metamorphose explores in text and image the relationship between nature and humans, the borderlands of living and non-living, and the isolation and alienation we have to face both in society in general and in current times. The series is inspired by the practice of Catholic nuns creating artistic dioramas using everyday household objects and domestic waste. It focuses on the objectification and distortion of the human form and the subjectification of the artist’s domestic waste material and the symbiotic relationship that is constructed in the process. All photographs are shot on Kodak Portra 400 and Ektar 100 film. In 2021, I will continue with a new graphic series – animated short films and sound, with the aim of installing an intermedia-exhibition that includes performance – and I will finish the prayer book. The texts are in Hungarian-English and German.

The story investigates how women’s health concerns, women’s bodies themselves, are unheard or misheard by the medical community, society at large, and even family and friends. –TB

What are you currently working on, Timea, and how do you see your work evolving in the future?

TB: I’m currently working on a short story collection of which “The Stone Men” and “What They Call It” are a part. It’s a collection of primarily magical realism that centers the narratives of Hungarian and Hungarian-American women, many of whom are immigrants, some of whom are queer, but all of whom are grappling in some way to gain acceptance of themselves, their identities, heritages, and/or families. The magical elements of these stories—be they animated men made of stone who stalk the streets of Budapest, a man made of mirrors who the city cannot decide whether to revile or revere, shadows that haunt the dome of the Buda Castle, or ten moons lurking under the surface of Balaton Lake—are directly relevant to these women’s fates, and are often agents for illuminating some important aspect of their stories.

In “A Stomach Full of Clenched Fists,” for instance, a young woman experiences hellish physical symptoms caused by the ghost of her recently deceased father who’s haunting her body. The story investigates how women’s health concerns, women’s bodies themselves, are unheard or misheard by the medical community, society at large, and even family and friends. While many of the stories are set in Budapest, like “The Stone Men,” or the Hungarian countryside, others play out out primarily on or inside characters’ bodies, like in “The Urge,” in which a woman crawls inside her fiancé’s chest.

The stories also engage in direct conversation with current and past Hungarian and global socio-political issues. “The Stone Men”, for example, draws direct parallels between the treatment of the animated statues and Syrian refugees now and Jews during the Horthy regime. The language barriers and code-switching inherent to immigrants’ lives also feature largely in these stories, taking center stage in cases like “What They Call It”.

The book is unique in that it’s the only short story collection written originally in English that centers the lives of Hungarian and Hungarian-American women. Along with Lesley Nneka Arimah’s What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky and the work of Sofia Samatar, it’s also one few short story collections about immigrants featuring primarily non-realistic stories. I’ve been writing it over the years as the project has morphed and changed shape. I hope it doesn’t continue to change shape on me, so I can finally finish it!

How my writing will evolve in the future I have no idea. I’m already writing poems in Hungarian, so maybe is fiction next? I hope not, only because it would be very time demanding for me, and even more so for those who’d proofread it, edit it. In any case, I’d love to see my stories in Hungarian, whether it’s me giving life to them in that language or a translator.

What do you both think counts as artistic relevancy in the era of Covid-19?

KT: Covid has thrown us all off balance and maybe also made us somewhat stronger. Our lives, circumstances and working conditions have completely changed. There are huge changes in every sector, and so are there in culture. New cultural, artistic forms are being born; we are using virtual space ever more deftly. On the one hand, this is sometimes the only option; on the other hand, we are experiencing an increasing lack of the personal. Culture has perhaps never played such an important role in making up for this lack of personal contact. Science and economic policies also devote special attention to this topic. Then there is another new phenomenon, the extreme form of turning inward. The question is to what extent can we and should we create art when so many constraints are imposed. There is an abundance of experiments aimed at this, we can also witness immersion and the act of turning inward, if I may say such platitudes. A need to work together has shown itself, and so has a need to withdraw; we are becoming more sensitive, and this might lead to new, better movements.

And you, Timea?

TB: The Irish comedian, film writer, and actor Dylan Moran says, “I’m alive now. That’s pretty relevant.” I’d second that.

Culture has perhaps never played such an important role in making up for this lack of personal contact. –KT

And finally, where are we in space and time as this interview ends? (Again, this can be literal or imaginary).

KT: At the moment I’m based in Hungary, I have been living at the aqb Project Space since the beginning of August. Originally, I was supposed to stay there till September, preparing for the exhibition and book launches, and would have begun my future programs in Switzerland in October. However, the uncertainty caused by Covid-19 has changed my plans for the year – for the umpteenth time – so I’ll definitely stay in Hungary till January. We’ll see what happens after that. I’ve been invited to Berlin, Switzerland, even here, to Budapest, and Graz, and I’m waiting for the results of a number of applications. So it is a beautiful in-between situation, but somehow even an arrival.

Timea?

We are at the end of a hectic week spent preparing to visit my partner in Vienna, who can’t get into Hungary right now since the border is closed due to Covid-19. Welcome to the second wave of the pandemic rollercoaster.

*** *** ***

Kinga Tóth writes and publishes poems, fiction, and drama pieces in Hungarian, German, and English. She is a musician and visual and sound-poet, and has presented her work around the world. Tóth’s book publications include the poetry collections PARTY, All Machine, Village 0-24, Wir bauen eine Stadt, and the visual-art catalogue Textbilder. Her novel, The Moonlight Faces, won the Hazai Attila and the Best Novel Special prizes in Hungary. English translations of her poetry have appeared in Poetry Magazine, Asymptote, Arkansas International, Dream Pop Press, and the Wretched Strangers anthology by Boiler House Press. She was recently a resident of the International Writing Program at Iowa. She is currently in the process of completing Corn Songs. You can find more of her work at http://www.kingatoth.com, www.tothkinga.blogspot.de, and Facebook.

Timea Balogh is a Hungarian-American writer and translator with an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. A 2017 American Literary Translators Association Travel Fellow, her translations of Hungarian poetry and prose have appeared or are forthcoming in The Offing, Brooklyn Rail, Asymptote, Waxwing, Two Lines Journal, Split Lip Magazine, Lunch Ticket, and the Wretched Strangers anthology by Boiler House Press, among others. She has short stories forthcoming in Prairie Schooner and Passages North and poetry forthcoming in Homonym Journal. Her debut original short story was published by Juked and was nominated for a PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. She lives, writes, and studies literary translation in Budapest. You can find more of her work at http://www.timeabalogh.com or tweet her at @TimeaRozalia.

Péter Tamás – who translated Kinga Tóth’s answers in this interview – holds a master’s degree in Hungarian Literature from Eötvös Loránd University (Budapest, Hungary) and is currently a PhD candidate at the Modern English and American Literature programme at the same university. The topic of his dissertation is Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. He is a Fulbright alumni.