Global Voices Interviews *Germany* Andra Schwarz & Caroline Wilcox Reul in conversation with LIT's JP Apruzzese

A dialogue between authors and translators

***

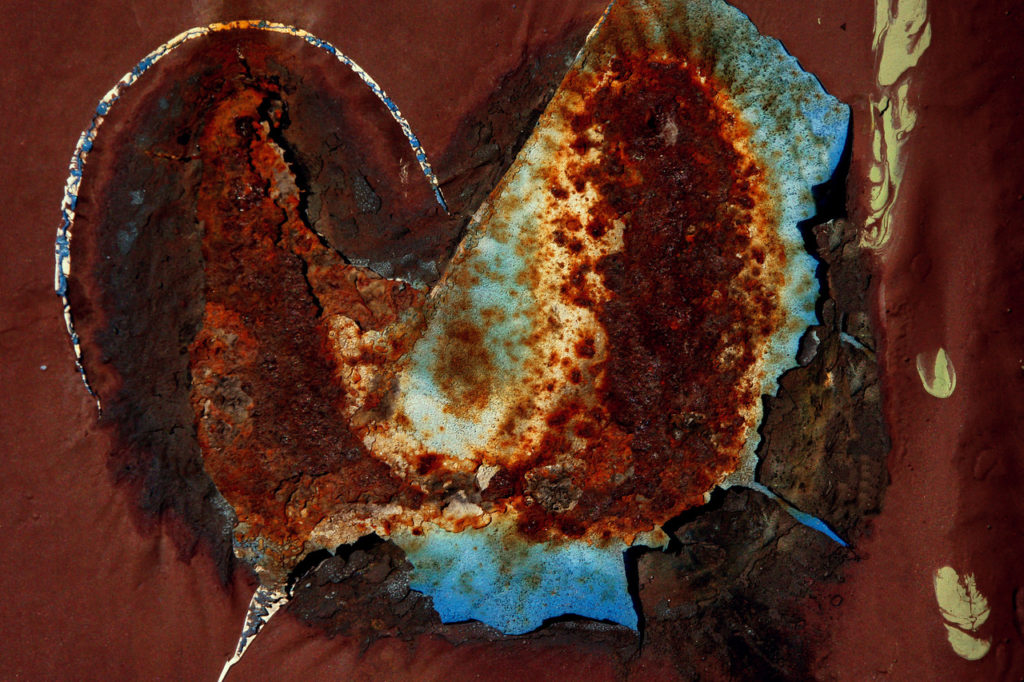

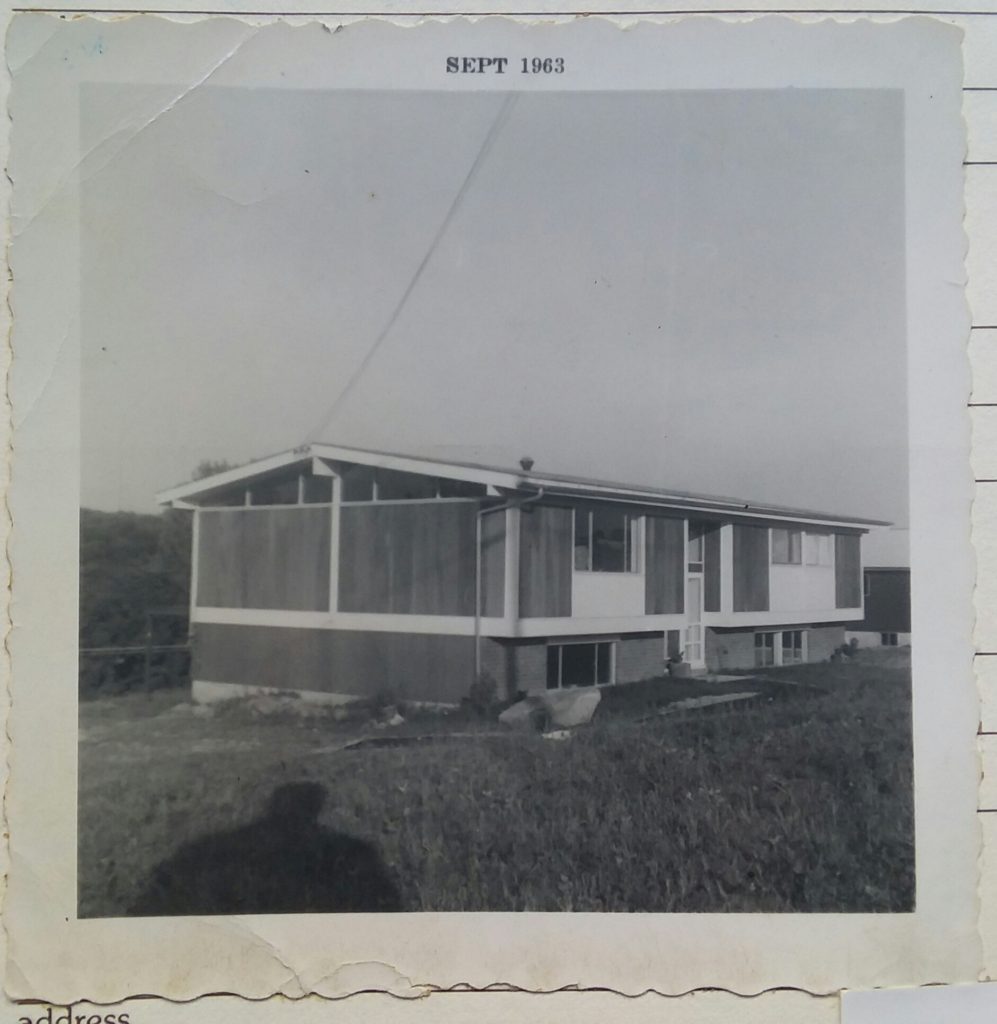

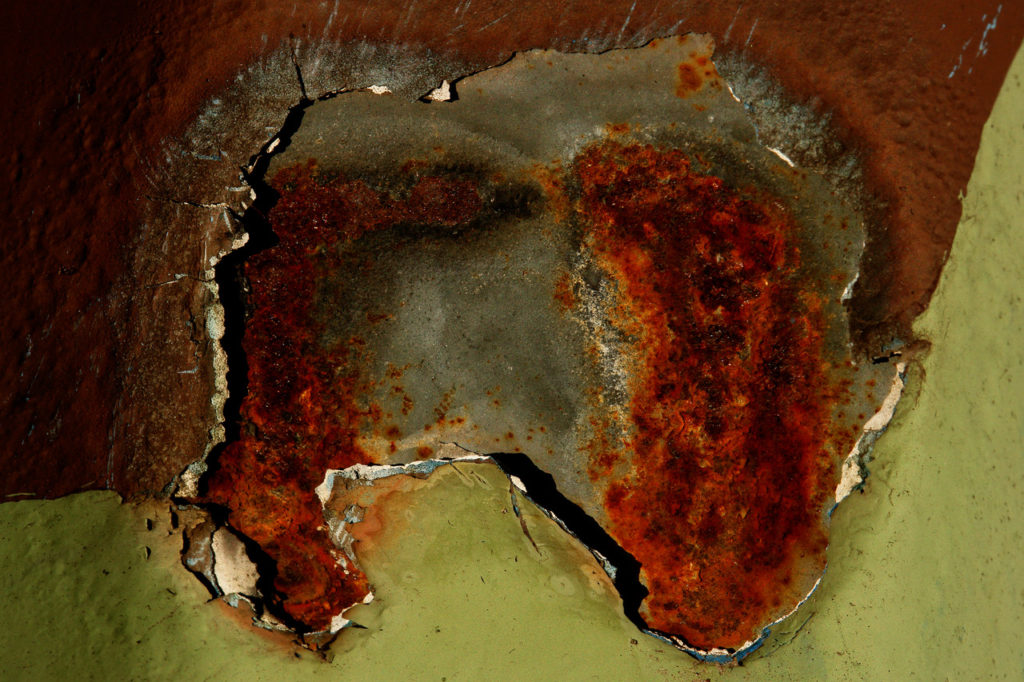

Last month Andra Schwarz’s poetry collection In the morning we are glass (Am morgen sind wir aus glass, 2017) was published in English by ZephyrPress thanks to a wonderful translation by Caroline Wilcox Reul. At LIT, we were delighted to publish five poems from Schwarz’s collection in March 2020. It is tempting when first reading these poems to assume they are about memories of a childhood home or reflections on the irretrievable past. This, however, would be a misinterpretation, one that does injustice to the deeper dimensions of Schwarz’s mission. If anything, the poems in this collection fall somewhere between archeological excavation and criminal forensics. A disappearance has occurred and the case never solved. The missing persons are Schwarz’s ancestors, the Sorbians, a German ethnic minority whose way of life and culture have vanished as a result of deliberate government policies of integration. The other – equally poignant – disappearance is that of the land itself, which coal mining and timber logging have made unrecognizable to those who once knew and loved it. Like many others, the Sorbians and their land ceded everything to the seemingly inexorable push of modernity.

Imagine you are standing in a place where a different world once existed but you are unable to see any trace of it in the new one. Now imagine you are told that that former world is central to who you are as a person, though you don’t know it. This is where Schwarz begins. She leads us through a place she has only heard of but never knew, a place intimately tied to who she is. The language of these poems inhabits this conundrum. Words back into words, phrases collapse into phrases, thoughts arise and fade into another, then suddenly pick up a few lines later. Here is a world where everything is revealed, or rather re-discovered, new and rich in meaning and complexity. Schwarz is the skilled archeologist who deftly reconstitutes that world as best she can, given the fractured pieces of evidence and the multiple, complex emotions that arise in her along the way. I was at first puzzled by the meaning of the collection’s title, “in the morning we are glass,” until it occurred to me that it is about transformation – the blending of one’s consciousness into everything that surrounds you, the way the words in these poems blend with each other and are transformed.

Getting this right in English was not an easy task. But as Caroline Wilcox Reul says in our conversation, “the work tells you how it wants to be translated.” It is this humility, this openness to a different way of seeing and understanding, that Reul brings to this collection and makes it stand apart. Mirroring the theme of these poems, Reul allows herself to disappear so that their full beauty and breadth and complexity can be gifted to the English-speaking reader. It is a gift because in reading these skillfully translated poems we can begin to see the disappeared worlds in our own midst – those taken from us and those we have taken.

*** *** ***

That which is no longer accessible, that which is absent

Andra Schwarz

So let’s start with you, Andra. You come from a part of Germany known as Lusatia, a borderland whose history and culture successive regimes throughout history have sought to erode and assimilate. How has your homeland defined you as a poet? How do you view attachment to a homeland in the current global context?

Andra Schwarz (AS): I grew up in the German Democratic Republic near Poland and what was formerly known as Czechoslovakia, a region that in the following decades was heavily impacted by the upheaval of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Factory closures and a high unemployment rate followed by hopelessness for the future led to a long wave of emigration from the area. This decline was a very painful process for many people in the former GDR, especially after the success of the peaceful revolution. The social structure was permanently changed, and it tore many families apart. These poems are, in this respect, an expression of that deep sense of uncertainty as well as the marks this time period has left in me.

On the other hand, through the fall of the Wall and the German reunification, I have had the opportunity to grow up in a democracy. That is an unimaginable privilege. In any case, I have gained a multidimensional perspective by having lived in different political systems and understand how fundamentally one’s background can determine one’s personal opportunities.

Homeland, for me, is not so much bound to a particular piece of land as it is to a language-based region because language, for me as a poet, is the point of departure for writing, and because of this it forms the roots of my identity.

Can you tell us, Caroline, how you’ve come to be a translator of poetry? What are notable personal experiences that led you to become a translator, in particular of modern German literature?

Caroline Wilcox Reul (CWR): I’ve been learning German for more than 30 years. It’s hard to know why German, as I studied other languages too – probably some combination of the language itself and what learning it has meant for my personal life. I didn’t have much support in high school and, to be fair, I wasn’t very interested in school either. So when I took first-year German in my early twenties at a local college, a new world opened up to me. Two years later, I spent my first summer in Germany on a study abroad program – that was 1989, just months before the Berlin Wall fell – and I loved everything about it, the people and their thoughtfulness, the food and drink, the lifestyle, the political tension, but most importantly I felt liberated from so much cultural and personal baggage I didn’t know I had. Through that experience, I learned I had options. Later on, I wound up living there for 10 years.

I began translating German poetry in 2016 when I moved back to Oregon and got together with an old friend who ran a publishing house that specialized in, among other things, poetry in translation. There was a German poet he wanted to publish, so I did some sample translations of her work, and my first book, Who Lives by Elisabeth Borchers, was born. I learned a lot through Borchers, who was not only a poet but also a translator and editor at Suhrkamp. She was a tough lady and didn’t mince words when it came to quality. Reading and re-reading a book of her essays based on lectures she gave at the University of Frankfurt toward the end of her career, and many interviews with her, I understood how she would want me to approach the translation of her poetry, and translation in general.

Language, for me as a poet, is the point of departure for writing, and because of this it forms the roots of my identity. – AS

Andra, you have gained the admiration of your peers and won awards for your poetry. Can you tell us about your trajectory as a poet?

AS: I developed an interest in poetry early in my youth and found myself turning more and more to writing and to exchanges with other writers while I was going to school for music. I later developed a desire to make writing my profession. After completing my degree in the humanities, I began to study “literary writing” at the Deutsches Literaturinstitut in Leipzig, one of the few recognized institutions for creative writing in Germany, and formerly an educational institution for authors in the GDR. This is where I met many fellow writers, engaged in intense discussions on writing, learned about various poetic forms, and developed my own style. This period of learning was an important time, during which my poems matured and I was able to find my own voice. More than anything, the quality of sound, by which I mean how the poem is realized when it is read aloud, what rhythm it follows, is an essential part of its inception when I write because poetry works under many of the same parameters that music does.

Congratulations on the English translation of your debut poetry collection In the morning we are glass that just came out this month. At LIT, we were thrilled to publish five poems in this collection in April 2020. Everything in this collection seems to reflect a search for a place and a time that have disappeared, as is aptly captured in the title of the first section – “The are no pictures of this place.” Can you tell us about the origins of this collection?

AS: A central theme in this poetry collection is disappearance, which recurs in different ways throughout the seven cycles of the book. It points to that which is no longer accessible, that which is absent. This experience of loss is reflected in and confronted by the process of recollection. Through the act of observation, something seems to slip away from the speaker so that they repeatedly attempt to connect with another in order to reassure themselves. The act of self-reassurance in the face of dissolving memory represents an essential component for the preservation of the speaker’s sense of identity. In this way, the poems describe a searching movement toward a self from the point of an earlier time.

The cadence of these poems gives a strong sense of borders butting into borders, thought-shapes backing into each other, like different orchestras vying for sound space. There are many voices speaking and yet in the end they are harmonious. It feels like a metaphor for current interaction among peoples and cultures. What has been your creative process?

AS: Borders form a central element in these poems. They touch on a fundamental experience of my childhood through the geographic proximity to the Polish and the former Czechoslovakian borders. Borders, whether territorial, scenic, physical or psychological, all cross the poetic space.

For me, border regions are places where various moments of temporality collapse to form a historical presence. I retrace their tracks in my writing and bring them together in the form of preserved memory. Applied to the speaker in the poems, it’s all about encountering and exploring places and their histories.

Through the pandemic, the majority of people have once again felt what limited movement through curfews, the restriction of personal freedoms, and the reinstatement of border controls within the EU can mean for our lives. At the same time, we forget as EU citizens that many people are affected by permanent restrictions to their freedom by autocratic governments and that they enjoy way fewer privileges. That is one of several important points that move me and motivate me in my writing to take up the idea of borders.

Border regions are places where various moments of temporality collapse to form a historical presence. – AS

Caroline, what attracted you to Andra’s work that you felt impelled to translate her poetry into English?

CWR: I came across Andra’s work on Lyrikline, a great resource for reading poetry in translation from and into many languages. The particular poem of hers I read first is called “Zeig deine hände” (Show your hands). There were so many things I loved about this poem: the imagery and the way it carries such strong emotional content, the economy and how much it increases the impact of each word, the way she uses what linguists call the ‘syntactic double bind’ to engage the reader’s mind in the same place of uncertainty the speaker in the poem finds themselves. The way every single word and how it is placed support the content of the piece. The poem insists the war is over, that one should let go, and yet it acknowledges the trauma that makes this directive impossible. This poem was all I could think about for days! And as I read more of her work, I found more of the same.

Your translations of Andra’s poetry collection In the morning we are glass are fluid and engaging so that we have the impression they were actually written in English. What has been your creative approach and process to Andra’s work? And how have you engaged with Andra in the translation process?

CWR: The challenge of poetry is that there is so much packed into so little that it’s like a world view in miniature. I love the process of climbing inside a poem, learning to live in its otherness, and then reproducing it from myself. As such, it’s an iterative and intuitive exercise, which I feel free to take my time with because, unlike with fiction, there aren’t that many words. Each one has to be right though, and that often involves finding something inside myself I didn’t know was there. Or more likely, something I didn’t have until the poem put it there. Also, I used to do a lot of lexicography work, so obsessing over a single word or phrase is one of my favorite things to do.

In general, I think the work tells you how it wants to be translated, but I do like to get input from Andra after I have a solid draft but before I begin to feel attached to the draft. Mostly, my questions are about the intent of a phrase or line, sometimes I want to hear more about what she was seeing when she wrote a particular line. Occasionally, we have to talk about the ‘plot’ of a poem which can be very humorous. In my experience, the translations are always better after discussion because my understanding of the work, and thus my translation, has deepened.

The work tells you how it wants to be translated. – CWR

Reading the poems in your collection, Andra, is like traveling and along with the narrator we are discovering a place for the first time. In fact, as Caroline mentions in her introduction, you call these poems Reisegedichte, or travel poems, yet the journey feels more like a rediscovery, even for the narrator.

AS: In this collection, the speaker returns to different locations – not physically but rather in memory. Memories offer up the possibility to observe one’s surroundings from afar, to rediscover them. This renewed encounter allows enough distance for its essence to surface, for example my sense of the mood of a place or an observation which moved me at the time and over a longer period matured within me until it became a poetic thread that I wanted to take up. In particular, moments of loss or leave-taking were salient.

Nature and landscapes are central motifs that serve as our first port of entry to this world and to the beings that inhabit it. This collection has an ecological spirit that places the narrator and the readers first and foremost in nature. Yet these poems point to the hidden destruction of that natural landscape by neglectful and myopic government policies and the forced displacement of peoples, your ancestors. Were you, through these poems, able to come to terms with this cultural and personal history?

AS: The labor of writing these poems definitely led me to confront my past, my family background and my Sorbian ancestry. Disappearance as a process, through which the landscape and villages of the Sorbian minority were destroyed in the extraction of brown coal, plays a central role in this. Seen through this lens, the poems represent an approach toward my own cultural-historical landscape – the question of its meaning in regard to my development. Being tossed back into one’s own past is key to this collection

Language is body, is movement, it not only allows movement, it also allows touching, physical contact. – AS

Interestingly, the notion of the search or the quest is felt strongly throughout the collection though we never get the sense we have arrived at the long-sought center. It is deeply reminiscent of the mythical and spiritual stories we find for example in the ancient classics. Is this intentional or did it emerge out of the process?

AS: The poems follow an impulse and attempt to recapture a place, a landscape or a person. The process of searching is articulated through the principle of dialogue in the poems. As such, memories are fragmented, vague. Language is body, is movement, it not only allows movement, it also allows touching, physical contact. And at the same time, examining the past allows the poems to float in a unique way. This phenomenon has been interesting to me as a poet for a long time.

CWR: For the poems in this book, and for Andra as a poet, sound is one of the more important qualities, and I felt it was essential that my translations had a similar acoustic flow. When I mentioned the classics in my introduction, I was mostly referring to the translation work of Robert Fitzgerald, which is so melodic with its iambs that it puts the reader in an aesthetic mode – open to the emotions of the work – even more so if you read it out loud. Longing, struggle, pleasure, and despair feel so immediate and impactful. It helped me find the right sound qualities to support the mood of Andra’s poetry.

At the same time, while reading Fitzgerald’s translation of The Aeneid, I was thinking how strongly our sense of identity is driven by our point of origin as a physical place of personal history, and how we embody that place with our memories. We orient ourselves toward, or away from, this place as we grow older. I think returning there allows us to synch up our various selves and experience a moment of continuity. Both Andra’s speaker and Aeneas experience a physical loss of the homeland. The latter as the hero in a hero’s tale transfers the energy of his loss into a quest for its replacement, his identity always solid enough to keep him moving forward. Faced with a changing, disappearing homeland, Andra’s speaker can only explore within themselves, within their memories, and seek out understanding of their identity, always vague, never graspable, the destination a starting point that is in the process of dissolving.

I see [Andra’s poems] as a kind of witnessing, a list-making of things stolen, and the people they were stolen from. You can witness and take leave without accepting the state of things. – CWR

In your introduction, you also capture the melancholy (bordering on tragedy) of Andra’s poems about the transformation of her homeland when you reflect on the perspective of the “current generation whose inheritance is only postmemory and the threat of future destruction.” Do you feel these poems come to terms with this change?

CWR: It is often the case when someone returns to where they are from or looks at old pictures, they feel an uncomfortable sense of “Did I really live here?” Was that little person in the photo of this place, or what used to be this place, really me?” As we grow older, our relationship with our place of origin becomes more complicated, not only because the place has changed but also because we are different people. This phenomenon is not what this book is about, though that feeling of estrangement is an excellent point of entry into this text. This book is about the resulting harm to real lives and the natural world when power and greed remain unchecked. It’s about the reality of loss and one’s attempts to find one’s bearings given that loss.

The poems in this collection take place in disappearing landscapes that are meaningful to Andra, her home region of Lusatia, and geographic locations eastward and to the north and south. But erasure and dislocation are all around us here as well. Mountaintop mining happens throughout Appalachia. Gentrification, pervasive in so many cities renders neighborhoods unrecognizable to their past inhabitants. Eminent domain dismantles and replaces. Villages lie at the bottom of dammed valleys. I don’t believe these poems intend to come to terms with anything but instead seek to acknowledge what has happened and its consequences. I see them as a kind of witnessing, a list-making of things stolen, and the people they were stolen from. You can witness and take leave without accepting the state of things.

The poems in this collection take place in disappearing landscapes that are meaningful to Andra, her home region of Lusatia. – CWR

So Andra, how do you feel about the translation of your work? Are there words and concepts you feel cannot be transmitted from one language/culture to another without losing something essential?

AS: Translations are a huge gift, especially because they offer us the possibility to become acquainted with other literary or poetic points of view, to expand our horizon of awareness, and to enter into an international conversation. With it, however, comes the problem of multidimensionality through metaphor and ambiguity in poetic texts, which can not always be translated into the target language adequately through equivalent vocabulary. Even here though, there are sensitive ways to deal with this and find appropriate solutions.

In this translation, one can sense the way the two languages are related as members of the same language family. I am especially impressed that in addition to the mood and the atmosphere of the poems, Caroline was also able to transmit the lyric tone into the English. That makes me incredibly happy.

Translations are a huge gift. – AS

And Caroline, how do you view the craft/the art of translation?

CWR: A couple years ago, I took part in a discussion of metaphors for the role of the translator. The one that sticks with me here is the translator as apprentice. I think it’s an approach that is humble and confident at the same time. It’s a promise to both listen and respond. This role may also be deceivingly egocentric because while Andra may get some translations of her work, I am the one who benefits first and foremost by finding new things inside me through an intense experience with the other. On a technical level, translating this book has been like a master class on brevity, on the effectiveness of speaking through omission, through silence, on musicality and rhythm, and so much more.

Have you engaged with Caroline in the translation process?

AS: Caroline reached out to me about two years ago with a few translated poems. A close and intense exchange between us developed quickly from there. Caroline possesses an incredibly sensitive way with poems, a great diligence, and a love for detail. Even more, I appreciate her as a warm and trustworthy person. I found our work together to be extremely fruitful and rewarding because Caroline’s questions caused me to return to the heart of the poems again and again, and through this, I was able to discover, along with her, the many aspects of a given expression. It is a blessing when someone takes the time to read poetry, and it is a stroke of luck when someone feels the desire to follow the poetic tracks of another in order to recreate them in their own language. I am beyond thankful for this gift that Caroline has given me with her translation of my work.

…the translator as apprentice. I think it’s an approach that is humble and confident at the same time. It’s a promise to both listen and respond. – CWR

As a translator, Caroline, do you feel, as some have claimed, that translation is the ‘art of loss’ and that some words and concepts are untransmissible from one language/culture to another? How do you approach what seems to be lost in translation and untransmissible?

CWR: I have a friend who calls language a ‘repertoire of approximations.’ From that point of view, every thought we have, as represented in speech or text, has already lost something, and I find this idea so appealing. Because if we were able to impart our notions, intact, to others, we’d lose all the mystery, all the wonder of being humans in community with other humans. One of my all-time favorite poems is called “Facing the Music” by Paul Auster. The poem’s speaker describes a day out in nature in starkly gorgeous terms, and how they desire to express that deeply moving experience to a loved one, knowing it can’t be done. Then come these lines: “more than the pure / seeing of it, I want you to feel / this word / that has lived inside me / all day long, this / desire for nothing / but the day itself, and how it has grown / inside my eyes stronger than the word it is made of.” If our emotional perceptions are the fullness of an experience or a ‘message,’ no verbal or written text can capture it all. In my practice, I find it helpful to work on the principle that translation is nothing more than another expression of that phenomenon.

As a woman translator, do you feel women bring something different to the craft/art of translation?

CWR: I feel reluctant to answer this question for so many reasons, so I will skirt it by saying that the best translations come when the translator can connect on a deep level with the point of view of the work. Since there are all kinds of works by all kinds of people, it’s not about gender, but about the process of selection on the part of the translator. I understand that this is a non-answer, but I am trying to get away from gender comparisons like this as I don’t think they serve us at this particular moment in time.

In your collection, Andra, we get the sense that you’re reckoning with Germany’s and Europe’s past, that you’re consciously a part of historical narrative. Where do you see your place within the world of German and European writers? And how do you see your work addressing the issues of concern in Germany, Europe, and the world today, especially in the shadow of COVID-19?

AS: In recent years, my work has focussed on poems about certain regions of eastern Europe, for example Poland, Georgia and also the Ukraine. The poems venture to sensitive locations in Europe and, through this, approach cultural and ethnic conflicts, political turmoil, and historically based upheaval. Conflicts such as the one currently becoming acute in eastern Ukraine, the hopeless situation in Belarus after the failed revolution, the increasingly nationalistic tendencies in countries such as Poland and Hungary preoccupy me. With these countries as an example, it is obvious how fragile and vulnerable democracy in Europe once again is. Authors have the opportunity to call attention to these occurrences and warn us of how dangerously close history is to repeating itself.

Can you share with us your influences, both early in life and now?

AS: Across the span of my poetic practice, my influences have not only come from poetic voices but also from work of other artistic disciplines such as the visual arts, dance, theater, film and music. I am also reading my way through different contemporary genres, without wanting to name particular authors, as my reading usually underscores a personal immersion in a particular topic. While contending with eastern Europe, the Polish poet Eugeniusz Tkaczyszyn-Dycki, whose poetry I admire, and his collection, “History of a Polish Family” have been accompanying me for a long time.

The poems venture to sensitive locations in Europe and, through this, approach cultural and ethnic conflicts, political turmoil, and historically based upheaval. – AS

And you, Caroline, can you share your influences, both early in life, in your career and now, within German and world literature and among writers and translators? And how have they influenced your writing and translation?

CWR: I find influences and thoughts that inspire me everywhere. I have been lucky to have had several great mentors in my work life. Although not a living one, Elisabeth Borchers, the first poet I translated, is a great example as I often felt during that initial translation that I didn’t have the tools to make conscious, smart decisions. The firm advice she gave, by means of her essays and interviews, offered me something solid I could lean on or deliberately reject. One assertion she makes: the translator needs to “overcome the fear of the goalkeeper facing a penalty kick.” Others include: the translator should approach their understanding of language with a measure of skepticism; it is the translator’s responsibility to discern where the text requires a light hand and where intervention is necessary; the translator should not let their imagination “get out of control”; the translation should be a “trusted echo of the original.” These may be simple pieces of advice, but at the time they helped me justify both creativity and adherence, to look for the spirit underlying the words, and to remain aware of myself as I work within it.

Every thought we have, as represented in speech or text, has already lost something…if we were able to impart our notions, intact, to others, we’d lose all the mystery, all the wonder of being humans in community with other humans. – CWR

How do you see the role of translation within literature today in Germany, Europe, and the world, and within larger issues of global concern?

CWR: In the metaphor discussion I mentioned previously, one role I had decided to keep in mind after finishing up my last project was the translator as curator. Which German poetry an English-speaking audience gets to read depends in part on whose work I choose to translate. That is a big responsibility and one I believe in. Besides loving Andra’s vivid and evocative work, I feel it adds to the current conversation on systems of power and their destructive nature. On the meta-level, western society seems to operate on the idea that what’s good for the ‘majority’ (I think this is mostly an idealization, not a real group of people) is good for everyone, or society at large. That view seems to be changing now as we realize that the either/or framework is a fallacy, and that often the opposite is true – what’s good for smaller-scale identity groups is good for all of us. In my role as translator/curator, I hope that presenting the particulars of Andra’s work reveals parallels and universals in the readers’ worlds. This collection focuses on the linguistic region of the Sorbian language, its people, the harm they have undergone, and the resulting consequences for them. Now English speakers can read this work and hopefully broaden their understanding of injustice and the abuse of power.

Andra, what are you currently working on and how do you see your work evolving in the future?

AS: I have been working on my second book for a while. The project takes up the concept of the uncanny which is negotiated in a poetically and aesthetically complex way. The poems serve as a projection screen and utilize different psychological traps like that of the phantom, the motif of the doppelganger, the dilemma or the tabu in order to pursue the eerie, that which unsettles. This is revealed in different ways – in mythological figures, chimeras, animals or as a child. In several poem cycles, the phenomenon is explored, reflected in thematic and stylized variations, and portrayed in its ability to transform. It plays with the motif of metamorphosis as a result of speaking metaphorically. The poems work with moments of surprise, discovery or disturbance in an intentional manner in order to impart the feeling of inescapable uncertainty.

And you, Caroline?

CWR: I am currently translating more work by the German poet, Carl-Christian Elze. He’s got a new book of poetry coming out next year and I am a little consumed by it. I also have an idea for an anthology I would like to work on with Andra that will take a lot of discussion and organizing before it can get started. I haven’t decided yet whether I want to be involved as an editor or as a translator, or possibly both.

And where are we in space and time as this interview ends? (this can be literal or imaginary).

AS: In speaking about the poems from this collection, I return to their point or origin (departure), to the moment of their inception, my attempts to search, to find. Poems generally come to me in the morning, still untouched by the events of the day. For that reason I would like to conclude with a line from my book, which is also its title, “in the morning we are glass.”

CWR: In a talk I attended, Zadie Smith said something I often think about. She said as writers we have to guard our writing time and hold it above all else. I have a full-time job in a library and a lot of other activities, so for me the time I must guard occurs on Saturday mornings in my room, which is where I am right now. The ceiling is high and the floor glossy fir. There is a small circle of lamplight. Nothing is on my mind yet. No one has entered my world yet today. Geographic location and season of time, neutral. Out there I can feel my friends, and my guy, and Andra, the flowers in my garden, the good beer I will drink this evening, without thinking specifically about them. Right now, my time is for this.

in this region abandoned by all but the stars

a northern light appears over the atmosphere floating

as long as the pulse beats we pause at the depth: goFrom “This is the end” by Andra Schwarz

*** *** ***

Andra Schwarz was born in 1982 in Upper Lusatia and currently lives in Leipzig. She studied creative writing at the Deutsches Literaturinstitut in Leipzig and was awarded the Open Mike Poetry Prize in 2015 and the Leonce and Lena Prize in 2017. Her first collection, Am morgen sind wir aus glas, was published by Poetenladen Verlag in 2017 and in English translation in 2021 by Zephyr Press under the title In the morning we are glass. She has received grants from the Berlin Senate, the Kulturstiftung Sachsen, the Goethe Institute Prague and the MuseumsQuartiers Wien. Her recent work has been published in the journals Transistor, Konzepte, and Mosaik.

Caroline Wilcox Reul is the translator of In the morning we are glass, by Andra Schwarz (Zephyr Press, 2021) and Wer lebt / Who Lives by German poet Elisabeth Borchers (Tavern Books, 2017). She was awarded the Summer/Fall 2018 Gabo Prize for Literature in Translation and Multilingual Texts. Her translations have appeared in the PEN Poetry Series, Lunch Ticket, The Los Angeles Review, Exchanges, Waxwing, The Michigan Quarterly Review, The Columbia Journal, and others.