I Promise Not to Behave by Sharon Mesmer

— after and for Lydia Tomkiw (US, 1959 — 2007)

You slip your purple glitter turban on,

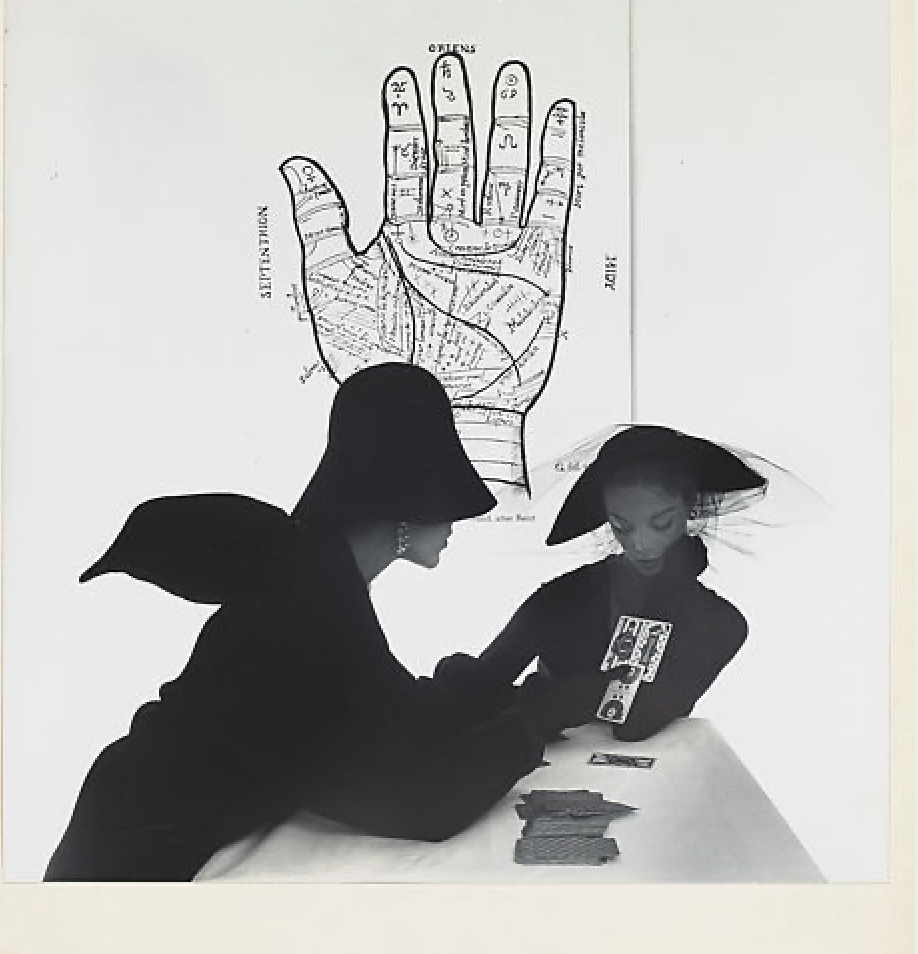

Spread my tarot cards on the table and whisper:

“I see a fever has crawled into you.”

I roll my eyes:

“Scarlet? Or yellow?”

You squint through the velvety knots of your lashes:

“Too early to tell.”

“What kind of an answer is that?” I demand.

“I don’t know,” you sneer,

“How many kinds are there?”

We’re in your parents’ kitchen on Oakley.

It’s a Friday night, and like every Friday night

A boy with a fork is tormenting a girl with a limp

In the alley behind the house.

I’ve just spilled vodka

On the major arcana . . .

— Okay, no, I haven’t.

We’re not in the kitchen.

You’ve been dead ten years and a day.

The last time I saw you alive was at the Astor Place K-Mart,

Wearing your purple glitter turban

And eating a hot dog.

Next thing I knew, a hazy, silent spectre —

Oddly shiny in the thin winter air —

Was stinking up my living room,

Poking holes

In the pink Brooklyn neon I called my own.

I didn’t recognize it as you,

But then two days later I got the phone call.

So I said a novena to Most Holy Lou,

Patron saint of ugly kids and dogs who chase cars,

Arranged my collection of salt shakers

Into a lagoon of mad lovers,

And conjured you up properly, from memory —

Pulling your turban down over your cherry-red bangs

Like you always used to on boardwalk nights

When the opposite of green unleashed new animals —

And made you speak.

Made you blame the current surplus

Of hesitation in my spine

On Saturn conjunct Chiron

Sextile unresolved adolescent ambition.

Made you hold up a card called “Delvaux’s Dream Girl” —

A nude sleepwalker glowing like a glass of milk —

And chant in your raspy, red rum voice:

“Soon a skinny black tie will be tossed

Romantically across a room,

And suddenly you’ll run out of arms

To wrap around all the young boys

And all the old boys

Kneeling before you

As you sit in a beach chair

Outside a cabana

Sulking.”

I knew that wasn’t what the real you would do.

The real you would take the side of my vile bridegroom

Who punched me in the stomach on New Year’s Eve

Because a stranger grabbed me on the subway.

The real you would — and did — say I had a screw loose

After I slit my wrist, after Vile Bridegroom dumped me.

And then you dumped me

For fourteen years,

Then expected me to be your friend again

After your husband dumped you.

While eating meatloaf in rehab you wrote me:

“We could be chainsaws under the stars.”

Under what stars? I wondered.

I never wanted to consider

Our interchangeable fingerprints again.

But soon there we were, just like before,

Sitting cross-legged on a curb

Fashioning mental movies

Of the story of our lives,

Our afterglow having grown cold

Long ago.

How could I have forgiven you?

Because I missed the days of falling asleep in your bathtub

As the sun came up.

I missed the mantic sway and swagger

Of being the first in our families

To graduate grammar school.

I missed our downpour, our clairvoyance,

Our simmering down into the breeziness

Of a summer night on a rooftop with nothing else left to do

After our liquid lips released the dream called “laundry”

From lockjaw.

You didn’t go clean, convenient,

Your lungs collapsing in unison,

Like you said you would.

You left a mess.

A mess heavier than the weight of all the waves

That kick themselves to death twice a day

Along all the seashores of the world.

A mess as tedious as your poem about me

Where I scrawl “Warsaw was raw” in lipstick

On an old lover’s letter,

Hold it up to a mirror and

Delight in myself.

A mess as ridiculous as our nicknames for the days of the week

(“Snowsuit,” “Thug,” “Aspirin”),

As calling each other on the phone during sex with our boyfriends,

And pretending the dull, Midwest rum-dums walking past the snack shop window

Where we sat drinking Royal Crown Cola and playing “Spot the Celebrities”

Were celebrities.

Ludicrous — like you actually being

Dead.

Remember splattering the classroom walls

With day-glo paintings of fish?Finding x-rays in the frozen dairy case?

Asking Allen Ginsberg if we could kidnap him

And get ourselves on the cover of Time magazine

— And Allen saying yes?

(Too bad we didn’t have a plan.)

How about hailing a cab at 4 a.m.

From the steps of the art museum

In the middle of empty Michigan Avenue

On Christmas

Just because it felt glamorous?

As if we already lived in New York.

As if we were already famous,

And not two working-class Slavic girls

Dressed in black, eyes lined in black,

Beneath a sky as vast

As we believed our futures to be.

Not wearing burnt furs plucked from a dumpster

And way too much “Night Blooming Jasmine” perfume.

Those were the good times.

They lasted about four years.

After that, calling what we had a “friendship”

Was like calling a beauty pageant

A “scholarship competition.”

But for those four years,

The beat of breath in our necks,

The flutter of blood in our guts

As we trudged out in knee-deep snow to buy condoms and pizza,

Assured us that in previous lives we really did sing hymns together

Until our brainwater ached,

Really did down brown whiskey and curse civilians,

Really were two restless rockets

Pretending to be flowers.

Does anyone still burn with a bright, jewel-like flame?

Does anyone still let all things happen —

Beauty and terror alike —

Unto them?

Is every great love still, in some measure,

A terrible mistake?

I hope so.

Because even death’s grim embrace is still

Life force, still blood, still breath.

Still bright.

Or so I believe.

Like when, against the black cosmic backdrop,

One winged brilliance arrives,

And mercifully blunts its own

Sharp shaft down

So as not to burn or blind us

Too much

(But just enough).

Can we please pretend

That the suburbs are prairies again?

That each time we blink

A million sounds escape from our eyes?

That the moon has no odor?

That there’s a hit TV show about us called

“The Two Little Polish Girls”??

That we never, ever looked at each other across a dank hall

And knew it would come to this?

Can’t it be October 1979,

And we’re under the El on Wabash,

Trading Edith Piaf albums for beer money,

And your finger is on the trigger of a toy pistol

That pops every time I shout

“Magnet!” or “Prune!”?

No, it can’t.

And I can’t make you read my tarot again, either,

Not matter how hard I pray and promise you

Not to behave.

It can’t be anything other than today,

September 5, 2017,

And you’ve been dead ten years and a day,

And I’m gray-faced and achey

And standing in front of your old apartment on Third Street

Next to the Hells’ Angels clubhouse,

Crying,

Because being alive

When you were alive

And we were new

Used to be so easy.

*

Sharon Mesmer is a Polish-American poet, fiction writer, essayist and professor of creative writing. Her fiction includes Ma Vie à Yonago (in French translation from Hachette Littératures, 2005), In Ordinary Time (2005) and The Empty Quarter (2000) and her poetry collections include The Virgin Formica (2008) and Annoying Diabetic Bitch (2008). Her awards include two New York Foundation for the Arts fellowships (2007 and 1999), and the 1990 MacArthur Scholarship given through the Brooklyn College MFA poetry program by nomination of Allen Ginsberg. She was recently featured on the cover of the American Poetry Review, along with her piece, “Flood the World with Beauty.”

The poem, “I Promise Not To Behave” is from a collection-in-progress called Even Living Makes Me Die. The collection responds to the lives and writings of thirty-five female poets of the Americas, from the 19th century to modern times. I chose these poets because they speak to me, in different ways, of the redemptive value of suffering. Many of these women’s lives were tragic: Some were murdered by lovers or committed suicide, some languished in lifelong obscurity — despite prodigious creative output — because their work was ignored or suppressed for political/cultural or personal reasons. As I read their work I began to write poems “after” them, to honor their brilliance and their struggles to be recognized. I was fully aware that I wasn’t “giving voice” to any of these women, as they had already spoken with courage and clarity about their lives. I was also mindful that I had a responsibility to “get it right,” to the very best of my ability. I took my primary cue from their work — I wrote only when I was inspired by the work — but before I wrote each poem, I researched each woman as fully as possible. I’ve included in this collection poems “after” women poets I knew personally. I met Lydia Tomkiw on my first day of college in 1978, and we were best friends on and off for many years. She died in 2007 of alcohol poisoning.

© LIT Magazine Issue #33, 2020